Welcome to A Closer Look, a new column at The Yale Review, in which we invite a writer to annotate a piece of art or an archival object. Mouse over the image and click on the blue circles to learn about the object’s history, provenance, and cultural relevance today.

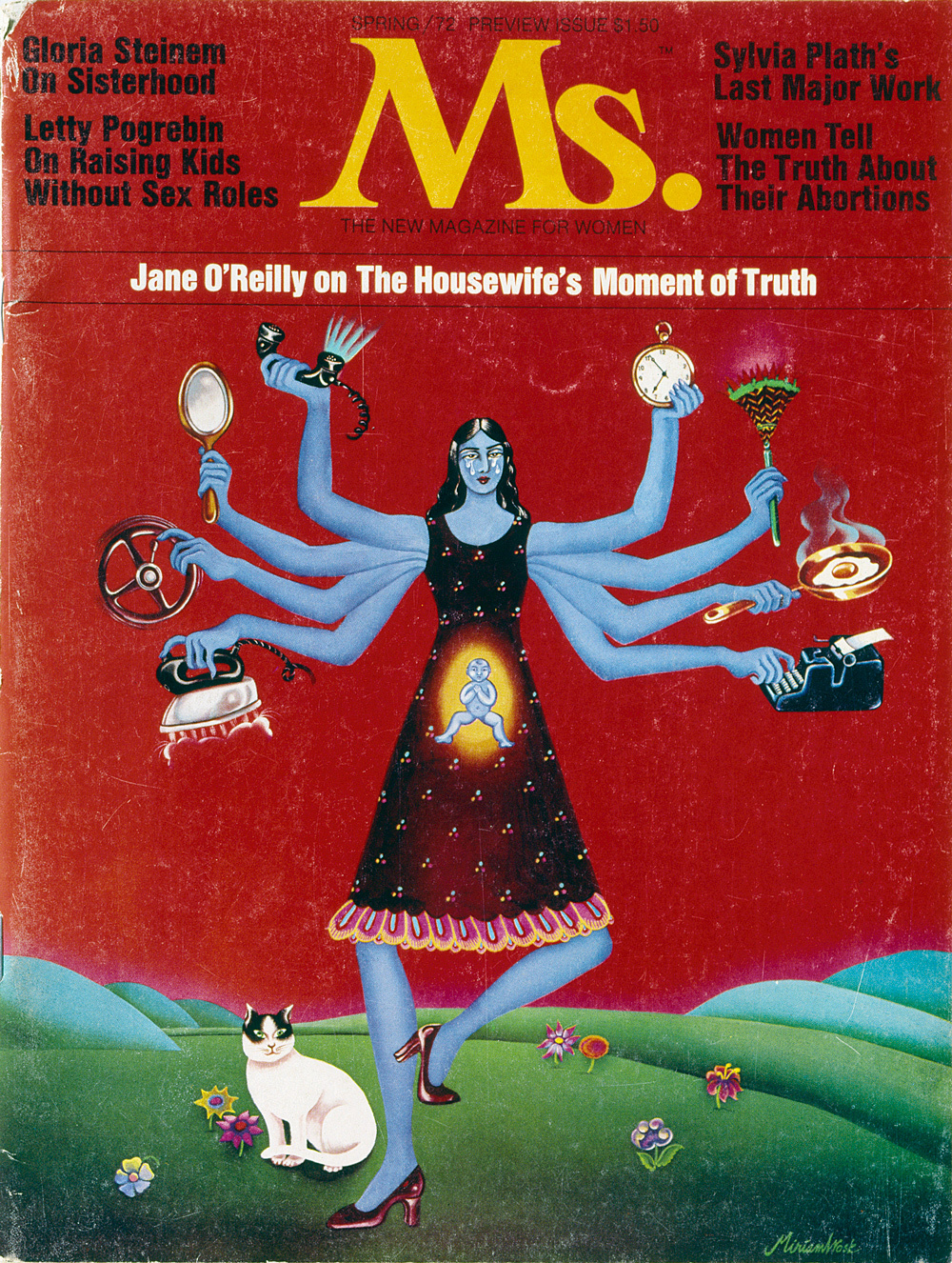

In our first installment, Maggie Doherty annotates the first cover of Ms. magazine. Read her essay on fifty years of feminist media in our fall issue here.

In December 1971, an unusual issue of New York appeared on newsstands nationwide. Readers flipping through its pages would have stumbled upon a forty-page insert, a preview of a forthcoming women’s magazine called Ms. Its tagline was “The New Magazine for Women,” and it was indeed new. Ms. was edited and staffed by women, unlike traditional women’s magazines such as McCall’s and Ladies’ Home Journal, which were helmed by men. The journalists behind Ms. understood “women’s issues” to include more than beauty lessons and homemaking tips. Gloria Steinem, Nancy Newhouse, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, and their collaborators hoped the magazine would win readers over to women’s liberation.

According to an oral history of the magazine compiled by Abigail Pogrebin, daughter of Letty, putting together the preview issue was chaotic. New York provided financial and administrative support, and in return its editor, Clay Felker, expected input on Ms., fighting viciously with Steinem over the cover design. (Felker once claimed he gave Steinem her first assignment because she had nice legs.) Advisers balked at a mockup offering a year’s subscription to Ms. for $6 and insisted the staff raise the price to $9 (roughly $66 today). There was no budget to advertise the preview issue, and much of the press attention that it elicited was negative; one columnist compared the tone of Ms. to “nervous fingernails screeching across a blackboard.” The magazine’s own editors planned for slow sales: When an expanded, stand-alone edition of the preview issue appeared in January, it was labeled “Spring 1972” so that it could stay on newsstands for months. As it turned out, there was no need for such hedging. The issue sold out in eight days.

The preview issue of Ms. remains one of the strongest of its fifty-plus-year run. (In an essay

for the fall issue of The Yale Review, I chart the longer history of Ms.—which is still publishing today—and its successor outlets Sassy, Bitch, and Jezebel.) Ms.’s debut included pieces on welfare, lesbianism, abortion, and how children learn gender roles. It also demonstrated how seriously Steinem and her collaborators took the politics of representation. The founding editors wanted all women to see themselves in this first issue. Paradoxically, it was an unreal woman—the Hindu goddess Kali—who provided Steinem with a cover image with which all women might identify.