On the night of May 23, 1968, at 12:15 a.m. the American writer and poet Henry Lee Dumas fell to the ground on a New York City subway platform. His soul stood with no shame. He watched the cop who had shot him grab a walkie-talkie with one hand and run toward him. Henry stepped to the side and smelled the cop’s starched shirt and sweaty underarms as he rushed past his ghost to his crumpled body. Stepping further back and examining himself from above, he saw his eyes were open, glassy. His face more dreamy than shocked. He thought about his friend Sun Ra’s sound argument against carrying his gun that day. The gun his friend Eugene Redmond had taken him to purchase after Martin Luther King’s assassination weeks earlier. He thought of the Babalawo in Harlem who taught him that the dead return to their origin city, the Ife-Ife. Visions came to his mind of his two sons, his wife, his mother, and his own origin city, Sweet Home, Arkansas. He knew he would haunt no one. He was gone before the cop’s knees touched the subway pavement next to his still-warm mouth.

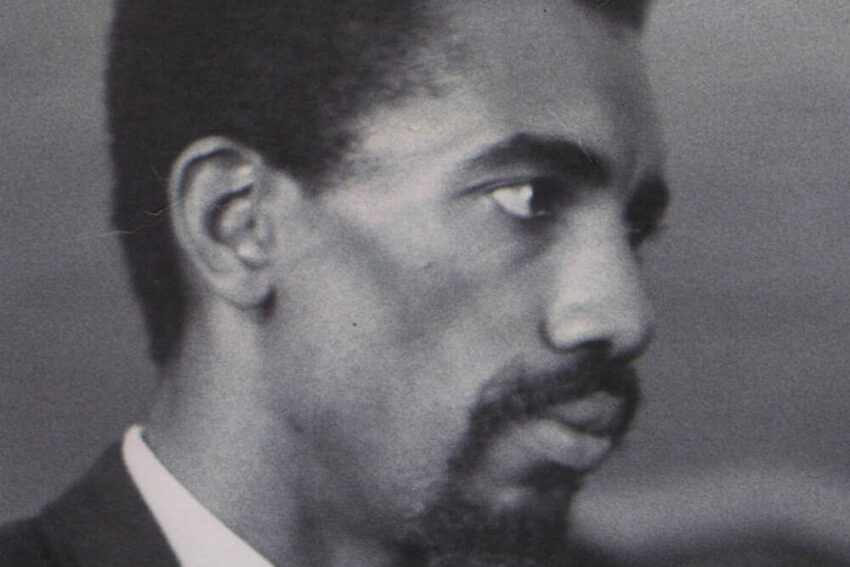

Of course, no one knows what really happened the night Dumas was killed. Although his spirit lives on through his work, the circumstances of his death, his death itself, and his work have haunted my family and me in the decades since. As Jeffrey B. Leak, author of the 2014 biography Visible Man: The Life of Henry Dumas, put it:

[Dumas] had traveled from his new home of East St. Louis to New York to serve as best man in the wedding of a friend. . . . On May 23, days after the wedding, a white transit patrolman shot Dumas after attempting to intervene in an altercation between Dumas and at least one other person on a Harlem subway platform. Accounts vary about the number of people involved, but it appears that Dumas was involved in a conflict with one person, and given the way in which the conflict evidently escalated, other people who were there felt in peril. The circumstances of the shooting were unclear, and after the passage of nearly five decades, many questions cannot be answered.

Dumas’s death was a heart-stopping caesura. An ellipsis made of bullets. A wholly unpredictable deus ex machina in the middle of what was becoming a great American writer’s biography.

It started thusly: Dumas was born in Sweet Home, Arkansas, in 1934. At the age of ten he moved to Harlem. After graduating from high school in 1953, he briefly attended City College of New York and then joined the Air Force. He was stationed at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. During this time, he met and married Loretta Ponton, and their union produced two sons, David and Michael.

My father, Eugene Redmond, met Henry Dumas in 1967 when he became a teacher-counselor and director of language workshops at Southern Illinois University’s Experiment in Higher Education, in East St. Louis, Illinois. Both men recognized the urgency of the transition from civil rights to Black Power and were part of its cultural arts component, the Black Arts Movement. As such, my father had heard of Dumas, and his work, before they met, and when they did the two colleagues instantly bonded over their shared Arkansas roots, using East St. Louis’s numerous soul food restaurants, bookstores, and bars as staging grounds for their conceptualization of the nascent Black Studies movement, of which they would each become early architects.

After Dumas’s death, my father refused to let Dumas’s work, which was so rife with ghosts, haints, otherworldly guides, and the overarching specters of white supremacy, rest. He recognized that Dumas’s spellbinding work would haunt him and the landscape of American literature, as he took on the important role of literary executor of Dumas’s estate.

My father recognized the value in bringing to life the ancient African knowing that informs so many of the young spiritful protagonists who narrate Dumas’s Afro-Surrealist worlds. For example, in the novel Jonoah and the Green Stone, Jonoah, the boy set adrift on the Mississippi à la Moses, knows that “the universe is sending a warning in drops that scream and splash like written words” and is later himself shot with a gun. The novel, now out of print, features a hero’s journey in search of a mythical green stone (magical watermelon?) that follows its protagonist through the contested identities of activist, hipster, preacher, and murderer. Or the voice in Dumas’s stunning verse, like that in his poem “Root Song,” which begins, “Once when I was tree / flesh came and worshiped at my roots.” Of course there is his much-anthologized story “Ark of Bones,” wherein Headeye, the boy-cum-priest, ascends in an “ark of bones,” ostensibly to the ancestral plane. Like Headeye, my father agreed to carry Dumas’s work—his bones—and for over 50 years he has lovingly edited Hank’s (which is the name those who knew him best called him) poems, short stories, and novel.

The notion of the body, and disrobing, was an idea Dumas turned to again and again. My father has said, “Hank used to say, ‘Take your clothes off.’” Some people saw it as a sexual thing. And some people understood it. If you’re truthful, then “take your clothes off.” Becoming fully naked for one another was part of the urgency of the Black Arts Movement, and Dumas sat at the nexus of it. His poem “Epiphany,” which was dedicated to my father, uses this vision of vulnerability in the final lines:

A man runs out into a field.

The sun is shining arrows.

The rivers of the earth

converge and fan out from

his feet and the mountains

east of the moon and west

of everything else

grow beneath his feet

and all the clothed

and feathered birds

watch him from the road

and the man takes off

joyously all

his clothes!

Their affection for each other as colleagues, friends, and writers was evident in Dumas’s summation of my father’s gift: “Redmond, you a writin’ nigger.” And it came through in my father’s work as a poet as well. In the poem my father wrote about flying from East St. Louis to New York for Dumas’s services, “Poetic Reflections Enroute to, and during, the Funeral and Burial of Henry Dumas, Poet (May 29, 1968),” my father observes, “Outside the skies cried for the dead black bard.” The poem also contains the despairing “I try in vain to figure out who I am.” That grief-fresh poem, originally published in my father’s book River of Bones and Flesh and Blood in 1971, chronicled just a bit of the struggle he and his generation of Black Arts Movement comrades waged against the backdrop of a horrific 36-month period bookended by the murders of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King and bridged by the systematic destabilizing program of the U.S. government, formally known as COINTELPRO.

Throughout his thirties, my father honored Dumas and his work, shepherding it through its first full-length publication via Southern Illinois University Press, until Dumas’s ghost jumped out of poet Quincy Troupe’s Harlem apartment bookshelf and into then-book editor Toni Morrison’s lap, as she sat cross-legged reading on Troupe’s floor. Morrison was immediately taken with Dumas’s work. She used it to introduce the one of the sections of political activist Angela Davis’s 1974 autobiography. She, of course, published it at Random House, and she goaded my father into an existential crisis when, faced with Dumas’s brilliant but unfinished novel, she said, “You finish it.”

My father has told me how he got that work done, but what he does not reveal in our talks is the gnawing uncertainty and the psychic weight of being “called,” as Headeye names it in “Ark of Bones.” What does it feel like to discover you are “The One”? Amid the all-night arguments about institution-building, Black Studies, Black Power, and Black nation-building, no one had prepared his generation of 20-year-olds for what to do when they kill your friend. How do you handle the practicalities of a family bereft—Dumas left a wife and two young sons—and the possibility of an income for that family from the work he left behind? Someone would have to take on gathering, polishing, and preserving the work, and it is a lifelong commitment.

My father’s own work centers on ancestorhood. His poems are often elegiac. It is impossible to know what sort of writer my father might have been, had his work not been so influenced by Dumas’s death. This work, like Drumvoices: The Mission of Afro-American Poetry, that is now an integral part of African American literature reading lists, serves as proof that my father is equal parts poet, scholar, and archivist. A deep commitment to Place has shown up in my work as well. The poems in my book chop, about proto-feminist civil rights warrior and native Mississippian Fannie Lou Hamer, are written in a form my father helped create—the kwansaba. It is a praise-poem form. I often joke about “going into the family business” when I tell people that I too am a poet and a professor. My dissertation features a close study of three poets, two of whom have written about Dumas—Margaret Walker (whom Dumas loved and whose work he would often “prescribe” to his writing students) and Jayne Cortez, whose poem “For the Poets” is dedicated to Dumas and Christopher Okigbo.

My father did not choose to be haunted, but he accepted the responsibility of the bones. I grew up being trained without knowing that I could consent to being haunted. We have agreed to steward the bones of our beloved from Sweet Home, Arkansas—and more if need be. Archival work, collecting and preserving delicate manuscripts, has been my father’s work. And when my dissertation crystallized, it revealed itself to be another side of the same jewel—collecting sound and parsing the ways performed work fits into the Black literary canon. I have an ancestor altar in my home. My father’s life is his altar, and I have been challenged by his example.

Dumas’s work sits at the starting point of Afrofuturism. In that technology, African spirituality and time are all at play. In “Ark of Bones” a character sees a year, 1977, that Dumas himself would not live to see. In a strange way, perhaps that part of it was intentional. One of the aims of the Black Arts Movement was to create institutions that would outlive their founders. This was also the aim of the founders of Historically Black colleges and universities like Howard University and my alma mater, Jackson State University. Both still stand today as a testament to formerly enslaved founders who knew they would not live to see the pinnacle of those achievements. Dumas’s work endures in this way, through the labor of my family as a service to the maintenance and growth of the canon, as a gift to descendants we will never meet.

At eighty-four my father has buried his parents, most of his siblings, and Henry Dumas before his time. As the patriarch of our family he keeps the stories. I have committed to recording those stories via a podcast we’ve created together so that the details are not lost. My father has promised to haunt me, which is how we like it. We warm under the glow of our ancestors’ attention. As Headeye was told, “[we] are in the house of generations. Every African who lives in America, has a part of [their] soul in this ark.”

It is possible that there will be an archive in the future born of my father's careful attention to one writer’s work. Dumas has given me a glimpse at a possible future. Without a lifetime of watching my father carefully steward the estate of Henry Dumas, I doubt I would think of legacy in the way that I do. To anticipate a legacy is to plan to be haunted in the best way, to create a solid container for ancestral creations that serves as a source for descendants and their community. Some have done this better than others. My father learned much of what he knows along the way. Now it is my turn to move from apprentice to journeywoman, taking the legacy, these polished bones, haunted as they are, even further.

Newsletter

Sign up for The Yale Review newsletter to receive our latest articles in your inbox, as well as treasures from the archives, news, events, and more.