I first encountered the work of S.L. in a group show at the Humboldt Gallery. S.L.’s three unframed paintings—luminous clouds against a bleak sky—hung side by side in an otherwise empty room, tucked away from the gallery’s main hall. They produced the effect of a portal opening from concrete to nature, from substance to air.

All three paintings were unsigned, and there was no mention of the artist’s name anywhere in the room, even though other works in the show were identified. I wrote to the curator the following day and received some basic information about the painter; I began following her work, striving to adjust my vision to the demands of her art. It would be years before I felt confident enough to write this essay, to examine certain aspects of her elusive technique.

My first contact with S.L. was as a guest editor for the winter issue of Dark and Moon; I wrote her to ask about using one of her pieces on the cover; the paintings I’d seen at the gallery some years before might work well, I suggested. S.L. asked what texts we would publish in the issue. I hadn’t told her that the theme was “Lost,” but upon reading the pieces I shared with her, she wrote to say that she did not think the cloud paintings were suitable, because she considered the contents of the journal “more labyrinth than dome.” She proposed a charcoal drawing of a forest path, which may also have been a large serpent, that immediately struck me as the right choice; the pieces in the issue, as she pointed out, were indeed labyrinthine.

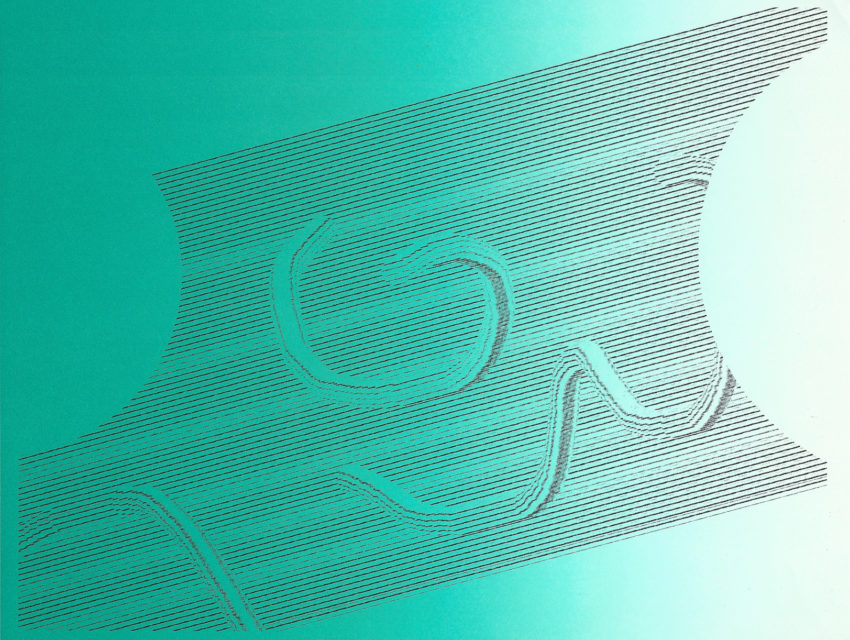

S.L.’s sensitivity to text is apparent in much of her earlier work, in particular her series Hawthorn, chronicling the meeting between a woman and six animals—fox, bear, wolf, seal, eagle, snake—inside a circular structure held up by pillars. The works are narrative in composition, both in the story they tell and the one they withhold: How did the creatures arrive there? What language do the woman and animals speak? They are also visually textual in their dense and sinewy surfaces—the echoing swirls, hatches, and strokes—as if S.L. has invented her own system of writing, a personal code that is at once decipherable and opaque, and might open up to a viewer with the correct focus.

Among S.L.’s influences are the writings of the early-twentieth-century Latvian parapsychologist Konstant¯ıns Raudive, whose life’s work was to capture voices of the dead in electronic recordings. Found in recordings of ocean waves, untuned radios, or microphone static, these voices, Raudive observed, “speak very rapidly, in a mixture of languages, sometimes as many as five or six in one sentence,” and “in a definite rhythm, which seems forced on them.” The sole work of the scientist, according to him, was to give sound to the inaudible.

This description resonates with S.L.’s art as well, where a mass of minute organic forms often transforms into human shapes. Within the silver-point series Kosmos is tree bark that has grown eyes, or the moss of a forest floor teeming with hands and feet. Everything is compressed, stuttering, making its way to us with immense effort, like the muffled voices of the ocean recordings. Viewers cannot be sure if what they see is indeed there, or a product of their imagination: is that the round, swollen shape of a breast? Is that a torso, dripping a luminescent saffron sheath?

Several critics point to a lack of intention and rigor in S.L.’s art, echoing a common critique of parapsychological studies that the human forms and voices they unearth are simply the product of the mind making familiar outlines of what it perceives. We are constantly searching for something to hold on to, the critics surmise; in the absence of meaning, we shape patterns out of pure chaos. As such, S.L.’s art cannot offer a new vision because it only mirrors the confines of the viewer’s mind rather than expanding them.

S.L.’s large-scale work Ode to Raudive may provide a roundabout answer. In more than four hundred canvases fitted side by side, the artist assembles turn-of-the-century ghost photographs alongside archival clippings gathered from laboratory transcripts, journals, and individual testimonies debunking the findings of the parapsychologists. There is a hypnotic presence in their abundance, even if it isn’t revealed in the fraudulent ghosts or their bitter rebuttals, but rather appears in the single-minded obsession with the invisible, on either side of the debate. Looping around the images is the repeated phrase, not without its own mystery, To Uncover What Is There.

Much has been written about the intersection of the corporeal and the spiritual in S.L.’s work, evincing a preoccupation with the artist’s use of optical manipulations, whereby the painted body gradually disintegrates to form a cosmological map. While S.L.’s technical mastery is certainly exceptional, such formal readings inevitably overlook her work’s most individual feature: her belief that it is not the artist’s but the viewer’s manipulation of art that is worthy of study.

In the weeks leading up to our first meeting for this piece, I asked S.L. to send me catalogues of her past shows, which I hadn’t been able to find. Several days later, I received a box of identical rectangular sketchbooks.

Of those, five contained pictures and photographs. Taken as a whole, the collection of images form the negative space of S.L.’s own work—a record of the artist’s visual intake throughout the years, the shapes, patterns, and colors echoing in surprising permutations in her work. Among them are drawings of tribal tattoos, busts, star maps and maritime charts, terracotta tile forms, cell structures, tree-bark prints, sketches of shells, corals, roots, and birds, and various studies of buildings with a round opening in their dome.

Four of the journals were herbariums, each plant identified in S.L.’s small, sloping handwriting. Some were collected from the hills and forests surrounding her studio and others from her travels, with samples of exotic species.

Of the remaining journals, all but one contained S.L.’s own drawings. These ranged from images of daily objects—paintbrushes, vases, bottles, bowls, fruit—to visionary drawings similar to the dreamscape of her large-scale works, with geographical formations that are at once familiar and fantastical. There is a sense of a spreading vibration, hushed in stillness, barely quavering beneath the artist’s lines.

The last journal in the box was a color archive. Each page was devoted to a single color, or two colors painted side by side. Looking at S.L.’s famous palette, as hypnotic as it is original, one has a contradictory feeling of seeing the color for the first time and knowing that the color is true, that it is the only one possible. Most surprising is S.L.’s use of muted and pale colors—grays, greens, violets—to vibrant effect, impossible to describe for readers who have not seen her work in person.

S.L.’s color combinations are equally surprising, appearing to be at once impossible and inevitable, due, perhaps, to the artist’s naturalist inclinations. She spends most of her working time outdoors, and the remainder of it simply sitting in her workspace. For her, the desirable state of creation is one of pure attunement, when she is able to register the smallest sounds and vibrations, so that there is no barrier between her surroundings and herself. “In this state,” she says, “I become the canvas.”

Our first meeting took place over the course of a whole day in S.L.’s studio. S.L. asked me to come as early as possible, and I arrived not long after sunrise. She met me at the door, opening it before I rang, dressed in a startling outfit. Once my sight adjusted to it, however, it seemed an obvious choice.

We walked through a long hallway to the main room, with a large kitchen and work space, and a half floor above it reached by a spiral staircase. The tall, curved windows of her studio open on to the hills and beyond to the forest, where the unique pines of the region rise to meet the skyline. The walls of the studio were pale blue when I arrived. By midday, they appeared gray. As the sun descended and light entered the studio at a stark angle, they were tinged with green. When I left, soon after sunset, they rang softly phosphorescent.

The workspace is entirely bare, with the exception of a large, oval rock on the table. Along one wall, drawers and cupboards fitted with many shelves contain supplies, collected objects, and S.L.’s drawings. S.L. joked, pulling open drawer upon drawer, that she was showing me the contents of her mind. She invited me to look through everything, which I did eagerly, finding unexpected sources of inspiration among her collection. I asked her why she had packs of playing cards tied alongside bundles of leaves. She untied one of the packs, spreading the cards on the table like a fan to reveal the faces drawn with miniature detail, and the saturated colors of the suits.

Her goal as an artist, S.L. says, is singular: “To contain the whole world within the work, everything that is interesting and beautiful, everything strange or out of place.” Painting allows her access to a previously closed realm, to multiple lives. Such liberty of the imagination, she says, protects the individual from the mediocrities of reality. She adds, however, that pure concentration is a more immediate passage to this realm than art is. It is the failure to retain this meditative state for long stretches that results in her work, not, as one might suppose, the other way around.

“Otherwise,” she says, “why would I want to leave that place and get back to paper and pencil?”

Her current project strives to move away from thought, which she calls “a decapitated existence.” But in S.L.’s inverted framework, such an existence does not mean the lack of one’s head but rather its overwhelming presence.

“The project is about undoing something that happened a long time ago. That moment in history when everything began to appear all too clear because we learned to perceive with our minds. This illusory clarity made us believe that total mastery was possible, if only we took up residency inside our heads. And the more we oriented ourselves toward this hope, the deeper we were trapped in thought.”

She hopes to move her art toward an expression of pure imagination, continuing to strip her work of the confines of sight, which, like thought, she considers an abstraction.

“It’s an amalgamation of many attributes that are mashed together as if they were a single entity. And yet, we’re constantly relying on it to ‘show’ us the real nature of something.”

From one of the drawers, she takes out a stone and asks me what she is holding.

I say that it’s a quartz crystal.

“You say that,” she tells me, “because you’re merging the sharp edges, jagged surfaces, the hue of the compressed strata, into a single form, which you call ‘quartz.’ But what you miss, in your mind’s clever and rapid calculation, is the essence that cannot be contained in a single convenient shape.”

I arrived for our second meeting soon after sunrise. Once again, S.L. met me at the studio door in her startling costume, rather like a hide, or a second skin, given how appropriate it was to her person. She told me upon my entering the studio, still bluish in the watery morning light, that she did not feel very much like talking.

She took out a long roll of paper, as well as pencils, ink, paint, and brushes and motioned for us to begin. We spent the rest of the morning in silence, with a parchment paper between us, on either side of the long worktable. The majority of the session was thus not recorded. S.L. worked standing up. Her hand floated slowly, and she did not put it down until we were finished, in the late afternoon, when the color of the studio walls had lightened and deepened, just like S.L.’s eyes, which shifted in hue as the hours progressed.

S.L.’s approach to drawing is to eliminate, rather than add. During our session, whenever she became interested in a line I’d drawn, she cleared out the space around it, sometimes with the use of complementary colors, other times with ink, magnifying my hesitant lines so that their underlying forms became unmistakable. By the time we were finished with our drawing, there was more space on the paper than there had been at the beginning, even if we had covered every part of the parchment. I was reminded of her cloud paintings at the Humboldt Gallery, how I’d felt that they functioned as a portal.

Before I left the studio she said that she’d enjoyed our conversation. “Some of these,” she said, pointing at a detail of lines expanding rapidly, then disappearing behind a wave of color, “are things I haven’t dwelled on in a very long time.” She added that she felt invigorated to get back to work, and I quickly packed my things to leave.

For our last session, she told me, she would be happy to show me some of the early attempts at realizing her current project.

Given the overwhelming interest in S.L.’s painting, surprisingly little attention has been paid to her singular essay “Artist Demystified,” which one critic has called an attempt to derail the audience. In the essay’s final section, S.L. tells an anecdote from her earliest childhood, with the stated hope that it may provide a point of entry into her work. What follows is a kaleidoscope of words and images that bear no discernible significance for the reader. Surely this is not a derailment—S.L. is rarely coy—but rather the firm statement that there is no direct entry into her earliest seed of consciousness.

In contrast to my previous visits, S.L. did not greet me at the door for our final meeting, but it was open, so I walked the long hallway to the studio. Inside all had been cleared away. Tabletops were bare, the drawers shut smoothly. Everything teemed with anticipation. Beyond the surfaces were the colors and shapes, lying in wait. Out the window, the dark tree tops in the distance floated like a storm, marking the place where the eye searched for clouds. My ears strained to make out the distant hum. I scanned the horizon, then turned my gaze back inside to the empty studio, where I stood alone. Just as there was no direct entry into the artist’s consciousness, there was no simple way to leave it, either.

The walls had begun their daily transformation.