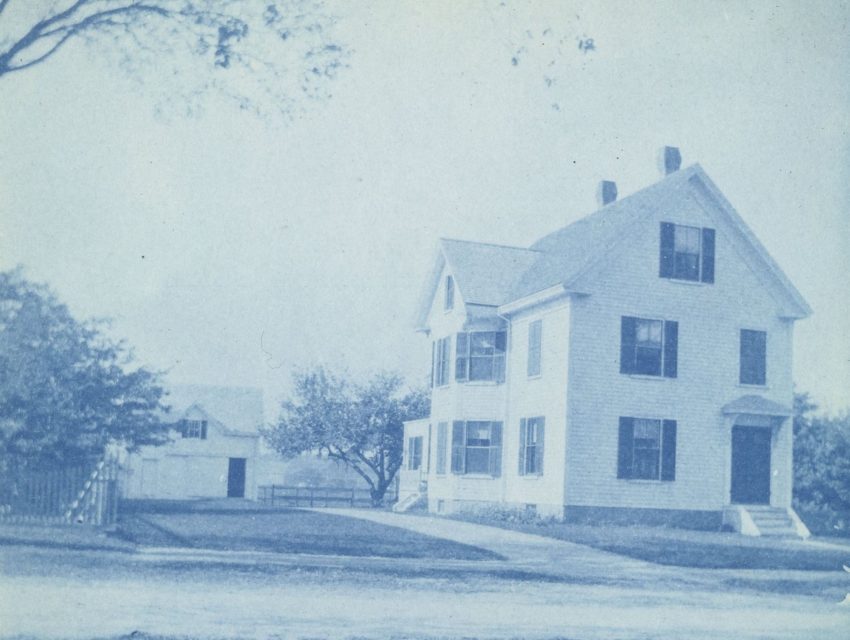

Late in the spring of this worrisome year I went for a walk in the countryside of upstate New York. From atop the hill, I got a good view of my friend’s large white farmhouse and its barn below. The pale blue sky was hazy, so the outline of the mountain range softened against it. Below, vegetable gardens with spoon-leafed lettuce and thin stalks of new onion unfurled in the mud. It was a particularly cold and wet spring, and the new grass flickered in a vital green, as if lit by the ground itself. As an invited guest at this farm, I felt emboldened to walk in any direction—that is, until I encountered the blacktop road that also served as the property line. Looking across it, I noticed another white farmhouse set far back from the road.

These two homesteads appeared peaceful, but either one of them might have contained guns. The land I was walking on originally belonged to the Munsee Delaware, who suffered nearly two centuries of assaults by settlers, including Kieft’s War, or the Wappinger War, fought from 1643 to 1645 with the Dutch. That conflict had a lasting impact on the Munsee’s security in this territory. While the Dutch used muskets to fight, the Munsee had been denied access to them. Another dispute along the nearby Esopus River in 1656 was hastened to its end by the spread of smallpox among the Munsee, leaving the surviving community at just a few hundred people. In the early 1800s, after centuries of violence, the Munsee sought to make a home in new lands jointly with the Stockbridge, a neighboring indigenous people. Together they relocated to Wisconsin in 1831.

Because this is the United States of America, guns remain an unresolved factor in the history of the landscape, including the vista I saw during my walk on that hill above the farm. They complicate my understanding of neighborliness and community, especially in places new to me. Just as I suspect some people who live in the country fret over being subjected to violence when they come to the city, violence is on my mind when I come into the country. Here’s what I worry about: What if I get lost? To whom can I turn to find assistance or direction? Where might I be allowed to rest as I make my way? As much as I want to embrace the walker’s right to roam, I know that to poke about or meander in unfamiliar lands comes at great personal risk.

I also know that much can be gained from changing one’s perspective, from going forward without knowing exactly where one is headed. I look at the blacktop road that separates the properties. In the distance I see a modest white farmhouse with its lawn of low-cut native grasses. Yellow wildflowers surround it. The gentle Catskill mountains roll and tumble into blue-green valleys beneath the shadows of clouds behind it. Nimbus, nimbus. Because this world is both familiar and unfamiliar, the words that come to my mind are open and free.

If I cross the road, I will have plodded past the boundaries of my own momentary entitlement. I will run the risk of trespassing, an offense for which the severity of reproach will be decided by someone I do not know, who does not know me either. The next steps in this journey are speculative, ancillary gestures offered to further the example. But before I proceed, let me put the guns out of reach, allow the homeowner to pull some other object of mechanical invention from the cupboard.

When I approach the house, a woman opens the door and asks me what I want. I say, “Excuse me, I am lost.” That’s when the woman asks me to leave. Though she is well within her rights, let’s say the lack of nominal pleasantries still stings.

Or let’s imagine that as I approach, I see a woman inside the house at the end of the dirt road pull a curtain back then beckon me to her door. Perhaps I was mistaken in seeing this gesture as an invitation; once I ring the bell, the woman shouts through the door to ask what I am doing here. I say, “I thought you waved me up—” but this does not change her disposition. She tells me to leave. I apologize for the intrusion and turn to go. The woman yells impatiently, “Go away!” and through a small opening in the doorframe she tosses a can of Campbell’s soup in my direction, just missing me.

Of course, the soup can is not a gun, though in this imagined moment it succeeds in delivering its own violence. A soup can, in this account, is a metaphor for convenience and consistency, for flavor preserved by heat and lightlessness. A gun is a metaphor for the damage the body cannot accomplish on its own. A can of soup must be heated to 248 degrees Fahrenheit, more or less, in order to be called sterile. The barrel of a 5-inch 50-caliber pistol will reach a temperature of about 275 degrees if fired twenty-seven times in less than four minutes, give or take. They are not commensurate, or interchangeable. Yet as emblems of industry, both items are stored within arm’s reach in the American household; their magnitude resides in multiplicity, in how easily they can be taken in hand, into so many hands.

There’s another version of the story in which the woman hits me in the back with the can.

There’s also a way to tell it in which I throw the can back at her.

Do I miss?

It depends on my aim.

I offer the lobbed soup can as a violent illustration of rejection and its related feelings. It makes me recall moments I have been turned away when I wanted to continue wandering: please leave this store, we will not sell to you; please leave this restaurant, we will not serve you; please leave this park, you are not welcome to play here; please get out of this cab, I’m not taking you anywhere.

Or maybe my issue with the lack of reception stems back to the time my family’s car broke down and we could not get accommodations in northern Ohio. Someone had told the manager not to give a room to the Black family waiting on the fuel tank repair. By this I mean that when we called to ask for a room, in all but one motel in the town, the proprietors said, “Yes, we have vacancies, but not for you.”

That act of racial discrimination was easy to recognize. Though I was a child at the time, the experience left an imprint on the way I think about travel. Eventually, thanks to an ambivalent innkeeper, we found lodging, but she made it clear over the course of our stay that we were not wanted there either. I watched my family compose themselves without emotion in the days we were stranded; I realized that the strangers we met were focused on their own sensitivities, most likely racial but perhaps prompted by other reasons, too, to care about ours.

The sensation I most often quell is the surprise of failing to be received once I have been invited in. It took me a long time to realize that many who extend welcome do so for the sake of their own conscience, rather than in the spirit of hospitality. If there is a term that encompasses the displeasure of this, I do not know it, though it is a part of me that I carry without the thought that I might ever put it down. It would be an overstatement to call it a burden, but its dull weight is easily recognizable. I know that I am not alone in experiencing it, and I must admit that I have never before heard anyone else say the word for it. Names for feelings can be tricky once they are pulled away from those who first claimed them, especially when power wants to diminish their significance. The feeling I am pointing to now includes being met with suspicion or scorn or worse. It’s the pinch of being subjected to someone else’s selfishness without consenting to it, of being forced to understand the world according to terms only they perceive as true. It’s the shame of knowing one may be shut out after all the effort it took to arrive, the door that closes in one’s face suddenly at the end of the arduous journey.

In mid-summer of last year, I drove with my husband and son through the northern Ohio landscape past the stop where my family’s car had broken down all those years ago. The glacier-flat fields with their magnificent green crops stretched across acres, so sturdy they seemed to sizzle and buzz. High blue skies with popcorn clouds moved in the percussive wind sweeping down from Lake Erie, a typical halcyon day.

While driving, I worried about our sixteen-year-old car faltering and was reminded that I don’t have much stamina for being read as an interloper. That is probably why I have always chosen to live in a city. Accepting my standing as an outsider requires me to acknowledge nuances I cannot anticipate, further amplifying my standing as a stranger. It’s like trying to comprehend a story that illuminates the edges of feeling by making a mere reference to it, as if to say the context is obvious. But people are not obvious. Until they are. With each motel sign I pass, I wonder about the hospitality of the proprietors: their temperaments and reservations.

My feelings about the Campbell’s soup can are complex because of nostalgia. The can reminds me of a time when I felt confident in my ability to explore alone the small world I inhabited between my house and school. I grew up outside Detroit. At the time, it was the type of community where one could win praise for looking and acting the same as the others, for consenting to and expressing appreciation of routine. I did not succeed in winning this kind of admiration, but the soup can represented my tastes during a period in my life when I was fortunate enough to feel certain about the boundaries of home and my place within it. Soup from a can was one of the first hot meals I was able to make all by myself, and for several years I filled my lunchbox thermos with it in the mornings before school; I ate the rest for breakfast. I collected the labels, and each month I faithfully brought piles of them in to my school, which returned them to the company for cash to support its extracurricular programs.

The Joseph Campbell company was originally located in Camden, New Jersey, founded in 1869. Its first product was a kind of tomato ketchup, made with beefsteak tomatoes, lobster, anchovy, mushroom, walnuts, mustard, cinnamon, cloves, mace, and vinegar. Shortly thereafter, Campbell partnered with Abraham Anderson, whose nephew John T. Dorrance came up with the idea for condensed soups. In 1900 the company’s tomato soup recipe won a gold medal at the Paris Exhibition; an image of that medal was proudly featured on the company’s label for decades, beneath the name “Campbell’s” in a script designed to look as though a housewife had written it on her list of essentials to gather from the market, and a row of fleur-de-lis—emblems of royalty—lining the bottom. By 1922, Dorrance had renamed the company Campbell’s Soup Company, touting its twenty-one nourishing flavors. Priced at a mere twelve cents a can, Campbell’s soup became a mainstay in kitchens where ease of use and consistency were prioritized.

My affection for the brand was enhanced by the fact that my great-aunt Beatrice—my grandmother’s sister—and her husband, Rodney, grew tomatoes for Campbell’s throughout the 1970s on their small family farm in the hills of Quakertown, Pennsylvania. Like my grandmother, my great-aunt Bea had moved north from New Orleans when she was a teenager, in the early 1930s, to reconnect with her father, who lived in New York City. But Bea was not long in the Bronx before she realized how much she preferred the clean air of the countryside. She made her way past the Poconos and never looked back. After her children were grown, she split her acreage with them, and they, too, built hobby farms adjacent to hers.

As a child, I delighted in thinking about her tomatoes being squeezed into those shiny cans. Blackberry bushes lined the far edge of her property. In the mornings we ate the dark, celestial fruit with heavy cream and boiled white corn on the cob. Even though I was a visitor, I felt at home in these hills, thanks to my relatives’ encouragement: they told me to go out, walk around, see what I could find. Those visits made me long for my own fields, made me believe I might find close relations and open doors in any direction I looked. This was not the only space where I would feel this freedom, but the comfort of being surrounded by family would give it the most impact.

A couple of years ago I gave a lecture at a large Midwestern university. I spoke in metaphors about isolation and discrimination with the hope that I would help people unfamiliar with those sharp sensations to feel them. In my talk, I referenced Herman Melville’sMoby-Dick. I pointed to his frustration with plans for U.S. colonial expansion through the Mexican-American War of 1846–48. Melville thought that the real goal of the conflict was to expand the number of states in which slavery would be permissible, including the territories acquired following the war.

I noted how he worried that the practice of claiming authority over these territories would inspire a constant anxiety in the minds of everyday Americans. A bit of, “If we could do it to them, who is to stop them from doing it to us?” I told a story about what it might feel like to be lost and unwelcome. Explicitly, I was speaking of the way cultural misperceptions inform an understanding of geography. Implicitly, I was pointing to how the impulse to withhold welcome might be read as anticipatory guilt for misdeeds yet to be committed.

Later in my talk, I shared a story I had made up about an angry and frightened woman in a white country house who threw a can of soup at me to get me to leave her property. I wanted the audience to see the way power can manifest in the use of everyday objects. I wanted to show them the overwhelming feeling that comes from being the last to notice that the terms of sociability have shifted. At the end of my presentation, a man in the audience asked me if the soup can was a reference to the famous series by the printmaker and publisher Andy Warhol. I explained to him that I rarely thought about the artist, or his series, even if I had included photographs of soup cans in my presentation. Despite my certitude, it took me quite a long time to articulate this, perhaps because I had not expected the question.

But in the hours after the event, I began to worry that my interlocutor had been right: that my soup can was a reference to Warhol, and that my commentary had not been about hospitality after all.

I took my husband, Danny, to the Museum of Modern Art one morning before work in early winter to look at Warhol’s paintings of soup cans. My hope was that I might discover how Warhol’s ideas about ease of access and repetition figured more overtly in what I was trying to suggest about power and boundaries. Warhol wanted to reproduce an image everyone recognized, and a friend suggested the soup can. The original series was completed in 1962 and consisted of thirty-two hand-painted images that are so similar they might have been stamped by a machine. I hoped looking at them might reveal a new way to think about the difference between similarity and repetition.

When we got to the second floor of the museum, the docent said that the prints had been loaned to another museum downtown, but she advised us to visit another gallery if we wanted to see a Warhol piece. Disappointed, we took the elevator up to the fourth floor. As we stepped into the gallery Danny gasped at the sight of Warhol’s The Last Supper (1986). This work features the image of a pink dove of peace, taken from the soap company of the same name’s logo, rising between a black-and-white illustration of Jesus at the feast. The branded Dove name stretches across the right side of the table, where Bartholomew, James son of Alpheaus, Andrew, Judas Iscariot, Peter, and John, or, as some prefer to believe, Mary Magdalene, sit. One of Jesus’s hands lies face down on the table, his other rests palm up. The space his hand makes in invitation, a bridge connecting disbelief and faith, is as magnificent and hard to measure as a universe.

Excuse me. How we hear this request for consideration also depends on our capacity to be generous in any given moment of our own suffering. Perhaps there is no better illustration of this than the Russian novelist Yuri Olesha’s short story “Liompa” (1928). In it, an angry old man named Ponomarev is dying. Suddenly aware that he will be powerless in death, he worries that he will become an abstraction, an idea contained by a name.

He resists this transition by proclaiming authority over all language. He tells the toddler playing outside his room: “Listen… You. Know that all this will be gone when I die, neither yard, nor tree, nor daddy, nor mommy. I will take them all with me.” The toddler, not yet able to speak, does not respond. Later, when the old man sees a rat in the corner of the room, he knows death is near. He tries not to remember the name of the rat: “He understood that he must, by all means, stop thinking about the rat’s name and yet he continued, knowing that at the very moment this nonsensical and horrifying name would appear to him, he would die.” The name that suddenly comes to the old man, “Liompa,” is a word that means nothing. Then the toddler calls out his first words, “Grandpa! Grandpa,” followed by his first sentence, “They brought you a casket.” In that moment, the old man becomes a memory.

The tale affixes a nonsense word intractably to the rat, the understanding of which serves as the threshold to oblivion. In real life, it can be hard to know where that line will appear or when one may cross it accidentally.

This is why I worried about my response to the man’s question about Warhol. This is also the reason I took my son to the Whitney Museum to see a retrospective on Warhol one Saturday late last winter. The exhibition included the artist’s famous soup cans. Though I was committed to seeing them, I was no longer certain of what they might tell me about my doubt. It turned out that the tickets I purchased had actually been for the next day, but the attendant let us enter anyway. Though the error in timing had been mine, the Black woman scanning the tickets said, “No problem, don’t worry about it,” as she stepped aside to let us in.

“No problem, don’t worry about it,” she had said.

All thirty-two soup can paintings—one for each flavor of soup—hung on the wall. Visitors jockeyed to get their pictures taken in front of them. The similarities in each image gave them a fatiguing din. I suspected, not for the first time, that obsession can be mistaken for admiration. Looking around the room it was clear to me that Warhol had his obsessions, and I have mine. Where they overlapped turned out to have been back in that university auditorium in Iowa, the space in which we welcomed a possible intersection of our perspectives. On our way back from the museum, we stopped at the store with the green awning and bought cans of tomato and chicken noodle soup from the man behind the counter who always addresses my son directly. After lunch, I stripped the labels off the cans and tossed them in the recycling bin.

When I spoke about Melville at the university many months ago, I had hoped to make clear that even though he was never overtly political in his sentiments, he rejected the values of Manifest Destiny and the spiritual imperative behind U.S. imperialism. And he remained guided by a code of personal ethics that remained firm, even as the common values of the country deadened around laws that represented explicitly racist concerns. Not long after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was written to end the Mexican-American War, the Compromise of 1850 was ratified, and California was welcomed into the union as a free state. But to balance the influence of slave versus free states, the agreement strengthened the power of the Fugitive Slave Act, which held that those who had escaped slavery could be forced back into it, no matter where they had established residency. In short, there was no territory that could be called “free.” And it encouraged all citizens to participate in this remanding of individuals, to be vigilant in identifying and capturing “fugitives” who had rejected the regionally determined infringement on their personhood. With this, southern states expanded their jurisdiction across the country, casting the shadow of trespass over all Black people and imperiling those who could not prove by papers or other means that they held rights to their own bodies. The compromise would set a permanent wedge in the Constitution.

Melville felt compelled to articulate the changes in the behavior of those close to him as they followed these new laws despite their own convictions. In particular, his father-in-law, a judge who had once been outspoken about what he believed to be the ills of slavery, began to enforce these new rules with unctuous consistency. Feeling a great sense of foreboding about the future of the larger nation, Melville witnessed the failure of individuals to hold to their own moral standards. He tried to write himself into a greater understanding through his characters. In his 1850 novel White Jacket, the titular character exclaimed after witnessing the assault on two Black sailors by whip at the hands of the captain: “Thank God I am a white,” and then, as an aside, “There is something in us, somehow that, in the most degraded condition, we snatch at a chance to deceive ourselves into a fancied superiority to others, whom we suppose lower in the scale than ourselves.”

As much as Melville wanted to know compassion, he could not write himself into it. Instead, his intellectual understanding of human worth affirmed his belief that restoring the practice of slavery in the northern territories would prove tragic. The Fugitive Slave Act, along with the violent annexation of much of northern Mexico, unnerved him and foreshadowed an unknown but inevitable catastrophe. This is not to say that Melville anticipated the coming Civil War, but he could see that the tensions that arise from so many strong, impersonal feelings, so many contradictory values, would not abate as a matter of course and that the as-yet unnamed conflict they might foment would be ferocious, possibly unending.

A world is made up of events, and time is how they fall into order. At this moment, more than 170 years after the end of the Mexican-American War, the U.S. government is constructing a bulwark across the border, that same landscape Melville worried about, to keep travelers who seek asylum, work, or reunions with family from crossing it. The wall is a visual affront to their ambitions, a fixture erected to diminish their will at the end of the arduous journey.

The land on which the wall is erected is also being damaged in this showy display of force. At Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument on the sacred lands of the Tohono O’odham Nation in Arizona, a bulldozer crushed ancient saguaro cacti and plowed through hillsides. Builders installed steel bollards filled with rebar and concrete to support thirty-foot-high wall panels outfitted with sharp edges and pinching slats. The resulting wall throws its shape across the map, shadowing the migrants’ points of arrival with unfriendliness, claims of trespass, imprisonment, dehumanization, family separation, and violence. People may one day look back at efforts to erect the wall and say that this was the moment the once-heralded expansion experiment failed. The lesson came in the form of a trick—for the wall was not only designed to keep the migrants out but also to change the terms by which to keep the settlers in.

Memories and nostalgia shape the future as much as they do the past, which is both about point of view and the facts of observation. My line of sight is informed by my access to a visible world. What I know to be important informs my emotional response to accident or injury.

On that overcast spring day in upstate New York, my friend’s white farmhouse called me down from the hill. Over coffee, we talked about our ambitions as our children plodded through the kitchen, dropping a muddy white onion from the garden on the table. In appreciation of their company, I wanted to tell my friends about what it had felt like to feel safe in another spot I once loved, a Lost Lake in northern Michigan next to a forest preserve, a quiet place much like this. At the edge of that boggy shallow smacked with broad lily pads, amid the guttural serenade of frogs, I sat in the evening’s solitude. The tall and spindly pines around the lake provided a momentary sense of shelter, a separateness from the expectations of others—that is, until I caught glimpse of headlights coming up the dirt road. A truck slowed and stopped its engine. The door opened then shut. In that moment between the sensations of peace and alarm a question appeared. It hangs there still. But I told my friends none of this. I let the story go with other thoughts about how disquiet comes to me: my feelings, my feelings.