Mother

Stereopticon

Twelve ways of looking at my mother

Emily Bernard

What is this word? I am three years old and perched on my mother’s hip. We are in the kitchen; my mother mans the stove. My legs hang around her waist, unanchored. I know she will hold me; she won’t let me fall.

I am holding a book. “What is this word? This word?” My finger moves along the page. Sometimes I peer into the pots on the stove, getting so close that my mother is forced to stop stirring. She sinks us into her seat at the head of the table, opposite my father’s. It’s just the two of us today, my mother and me, which will forever be the way I like it. I did not know it at the time, would not know it for years, but every morning she sat in this chair and worked on drafts of her poems.

“You wouldn’t let me cook!” my mother complained the final time we saw each other. She complained every time she told this story about the two of us in the kitchen, and she told it often. Beneath the complaint was pride in her daughter, but also pride in herself, for the balance she had struck, mothering, teaching, and tending to her family, all at the same time.

She offered this story to me whenever I needed to be reminded of her expectations, of the determined woman she wanted me to become. I don’t remember this story, but it is the story of my life, of my mother and me, our primal connection. For many years, I believed this ability was the sign of a true mother, a good mother: someone who executed the job seamlessly, and always put other work aside until the work of mothering was done. For years, I thought this image a portrait of my destiny, my rightful inheritance as the daughter of a mother who seemed born to the role.

The story never changed, but my mother’s reading of it did. The last time we talked, she told me she had come to believe that the reason I was leaning so far over the pots wasn’t that I was born hungrily searching for stories but simply because I couldn’t see. I was prescribed glasses a few years later.

Visions

I have always been fascinated by a bizarre event Zora Neale Hurston recorded in her 1942 autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road. She was sitting on a neighbor’s porch when she was beset by a series of visions, which she described as twelve “clear-cut stereopticon slides.” She was terrified by what she beheld. “I saw a deep love betrayed,” she wrote, “but I must feel and know it.” There was no escape from the drama ahead: “I knew that they were all true, a preview of things to come, and my soul writhed in agony and shrunk away.”

I have read these passages to audiences before, but since my mother died, I have never been able to get through them without crying. This story is my favorite in the entire autobiography, which I first read during my freshman year in college. I later read this scene to my mother. I remember the look on her face, both satisfied and intrigued, as she put her finger to her lips and looked away. I had known the lines would speak to her—that we were drawn to the same thing, the promise that no matter how painful, life was always unfolding as it should, and it was possible to view all of it with the cold, clear eye of acceptance. There was something comforting in the strange promise that our lives are not, in the end, a consequence of chance or even choice, but the indifferent hand of fate at work.

HOME

"Let's go so we can come back" is something my mother would say. I teased her whenever she said this. It perfectly encapsulated the most important feature of her personality.

Over the course of 30 years, out of the many rooms of my father’s house, my mother made a home. It thrived in the kitchen, which she organized according to her skills and idiosyncrasies. It flourished in the living room, where she sat at her secretary, composed poetry, and kept up with correspondence. It bloomed in the rec room and garden, in the lush plants that she cultivated as carefully as she did her children. By the end, my mother had wound her life down to two rooms: the room my brothers had shared as children, where she kept her books, and my old room, where she hid her poetry. She kept everything until the end.

My mother preferred being at home, and I preferred being with my mother. For both of us, the social world was largely an intrusion. Most people were strangers to her, even those she called friends.

In the seven years following her death, my father turned my mother’s home back into a house. It was gradual, and all at once. It was as if I left a living home one day, and on the next, I returned to its carcass, a house whose interior was shadowed in cobwebs, dank with mold, and littered with dead mice in my childhood dresser drawer. But I don’t blame my father. He had depended upon my mother to tend to the organs, soul, and lifeblood of our lives while he took care of the hull. Every marriage, perhaps, is animated by a contract, spoken or unspoken, and this was theirs.

THIRTEEN

When I am on the road giving readings and people ask me how my children are, I say, “How are my daughters? They’re 13.” Everyone laughs. Not everybody has been a parent, or a daughter, but everybody has been a teenager.

My twins became teenagers one at a time, Giulia then Isabella. It was as if one minute they were children and relatively easy to control, and the next minute they were snarling adolescents with unpredictable emotions. Early in the storm, I was preparing to take Giulia home from a violin concert. She was on the way to the bathroom and I was standing in the hallway, chatting with a fellow parent.

“We’re heading home. I’m just waiting on Giulia,” I said. Giulia whirled around and walked back toward me. She stopped and hissed, “I told you not to wait for me!”

I was stunned, hurt, and embarrassed. I ended up driving home by myself while my husband John, who had come early to help set up, took the kids in his car.

I took my time. When I arrived, I dropped off the things I had promised to bring with me, and then turned around and left again—but not before, with great flourish, placing my phone on the table beside my bed, like a clue.

One of the things I inherited from my mother was a belief that I could force sense out of life on the page.

I drove for hours. I went to a bookstore, the small town where I attend church, and my office at the university where I teach. I went to one Starbucks, and then another. While I was driving, I thought smugly of how much everyone at home was surely missing me, learning the hard way how much less delightful the house was without me in it. I kept driving. Then, I started to worry that my absence was causing alarm. I imagined John calling the police, the hospital. I could hear him yelling to the girls, “Where is Mommy? Has anyone seen Mommy?” I could see the girls searching for me, demanding of John, “Where is Mommy?! Why don’t you know where Mommy is?” I pictured them calling my phone, following the ringing upstairs to my bedroom, spotting the phone on the table, imagining terrible scenarios. I panicked. What was I thinking? This was a horrible idea. So cruel! I sped home.

When I opened the door, I could tell immediately that everything was just as I left it. No one had called the police. I sat on the edge of my bed and checked my phone. No one had called me either. No one even noticed I was gone, except for Giulia.

I was lying in my bed feeling sorry for myself when Giulia entered.

“Where did you go?” she asked.

“I needed to get out of here,” I said.

“Why?”

“You know why.”

She was silent. “But you needed to get away from us.”

“I am still a person,” I said.

She lay down next to me so that we were parallel, separated by pillows and blankets but together. I thought she might ask me more questions, about life, about being a mother who was also a person, but she didn’t. I was grateful because I had nothing to add. I wanted to enjoy her presence, so peaceful and so close. I knew it wouldn’t last.

“I’m sorry,” Giulia said quietly after we lay together in silence for a good long while.

“It’s OK,” I said.

Then Giulia got up and left the room.

TWELVE

It is not a coincidence that Zora Neale Hurston saw twelve visions. In ancient times, twelve was considered a perfect number. Hurston had grown up in the church, her father was a preacher, and the number has biblical significance (twelve apostles, the twelve tribes of Israel, for example). The images that appeared before her were compelling, but Hurston was also interested in the idea of a life foretold. “The vision is a very definite part of Negro religion,” she wrote. “The vision seeks the man.” The story finds its form.

Many fans of Hurston’s work don’t like Dust Tracks on a Road. It is not a true autobiography in that Hurston does more concealing than revealing. She leaves out years and husbands. She loses track of the visions. There are holes where the stuff of her life should be, the things she didn’t want to tell. But if you can’t take liberties with your own life story, then really, are you free?

I gave my mother Dust Tracks on a Road on her 48th birthday. It was the summer after my freshman year in college, where I had taken a course on African-American literature. Neither my mother nor I had ever heard of Zora Neale Hurston before I took that course. My mother went to Fisk University in the 1950s, where the emphasis was on classical education. She didn’t take the one available course on African-American writers. Even at Fisk, African-American literature was not considered a serious subject in the 1950s. Her peers snickered and referred to the course secretly as “nigger lit.”

I teach African-American literature. Today, such a job is not unusual. I teach and write about race. I care about literary legacy and inheritance. But even more, I care about the shape of a story. I like lines, gaps, and blank spaces, all of the things that can’t be captured in language, whole lives lived in grace notes. The form is the story; the story is in the form.

“I am excited for her to get it,” I wrote in my diary about Dust Tracks on the eve of my mother’s birthday. “Only, will it be enough?”

WHITE CASTLE

It was a tough summer, my mother’s 48th. My mother was learning new things about her marriage and her power. I was, too. A week after giving my mother Dust Tracks on a Road, I had a fight with my father that changed my life, or at least the way I saw it.

It happened at church. My father: laughing and reminding everyone within earshot that I was about to be a sophomore at Yale, home for the summer. “The usual cute Bernard family hype,” I recorded in my diary. It was August, the day before my nineteenth birthday.

At coffee hour, Dr. Edwards, a colleague of my father’s whom I admired, asked me about school, what classes I was taking, what my plans were for the future. She asked if I had a boyfriend. She talked about men and all their shortcomings. I nodded my head, hungry for her approval, hoping my furious nodding would conceal my ignorance about men. “Men are afraid of intelligent women,” she said. I agreed. Suddenly, my father appeared at my elbow.

“Be quiet,” he said. Be quiet. Hatred bloomed in my chest. “He said that women use that explanation as a cop-out because their personalities are not pleasing—to men, I guess,” I wrote. A welled-up, long-denied anger surfaced. To my shame, I cried. “I can never beat him, never show him how wrong he is.”

After church we went to brunch. A rare treat—my father was as cheap and tight as a fist—it had been planned for my birthday. We seethed at each other, silently daring each other to resume the fight, as the waitress seated our family.

Then the argument took an odd turn. “So, you think your mother isn’t intelligent?” Our eyes met. I was dumbfounded; my mother was, too. I tried to clarify what I meant, but quickly gave up.

Later that day, my father instructed my mother to inform me that he would not send me back to college unless I apologized.

“I am free!” I rejoiced in my diary. “I don’t have to finish school, go to graduate school, marry a nice black boy or even be a good girl. I can be mean and ugly and let my teeth rot and my voice grow screechy.” Even my handwriting looked freer. “Everything is out in the open. There are no more secrets to be kept.”

But I wasn’t free, after all. Or rather, freedom would have cost me more than I was willing to pay.

My mother took me for lunch a few days later. It was a Saturday. Her eyes were rimmed red, her gray hair frizzy at the temples. White Castle: it was our secret guilty pleasure. I had to apologize to my father, she said.

She could barely meet my eyes as she instructed me on how to shape the apology and what posture to take. I knew how much my education meant to her, much more than it meant to me at the time. My mother believed in education the same way she believed in God.

“She let him break her,” I wrote. Her tears merged with mucus as she bit into her sandwich. She told me that she couldn’t help me.

My father won. I apologized. He reminded my mother and me of his power. And I learned to keep myself a secret.

TWO MOTHERS

“He changed,” my mother said when I asked her why she had ever married my father. She changed during their marriage, too.

I kept a diary to record what I was seeing. The act of narration—of arranging life into a story—preoccupied me. I was focused on that task above all others. One of the things I inherited from my mother was a belief that I could force sense out of life on the page.

And so from the age of fourteen I began to keep a record of the changing shape of my parents’ marriage. One record I made I titled “Two Scenes.” The first scene was a story my mother told me when I was an adolescent and stoking dreams of becoming a writer. It is about my mother as a protégé of Robert Hayden’s, how she would accompany him to readings where she would recite her own poems as an opening act.

The second scene was an attempt to capture what was unfolding in real time, right in front of me: my father firing back at my mother, who had insisted, in her quiet way, that there was something wrong with the brakes in her car. “Who do you think is going to pay for that?” said my father. My mother went silent.

Was it true that she didn’t have access to enough money to pay for her brakes? That seemed incredible to me. She managed the books, after all. But she received an allowance from my father, I would learn later. She controlled the money, but she did not control it. I was a teenager when she started to warn me, “Always have your own money.”

There was my mother, the twenty-year-old budding star. And there was my mother, the forty-six-year-old woman cut to the quick by my father’s words.

I stood in the doorway and watched. My father’s triumph. My mother’s silence. Why didn’t she say something? All I could do was write it down.

THE SLAP

My mother encouraged my brothers and me to write poetry. Early on, I learned to take criticism. My mother was exacting. One day, as a test, I copied a poem out of a magazine and tried to pass it off as mine, just to see if she would know the difference. I wanted to see, just once, what it would feel like to write a poem that she praised right away, before the multiple drafts she demanded of me. She read the poem, handed it back, and looked at me. She knew I was lying.

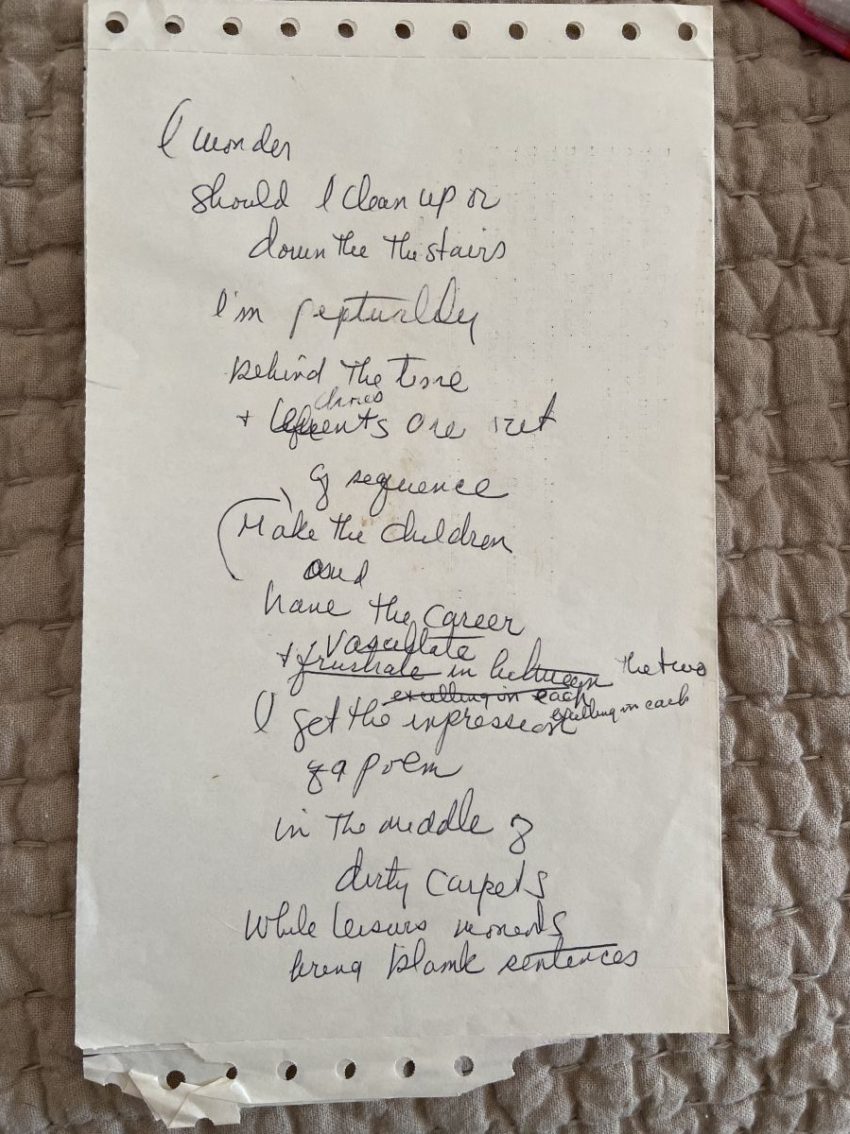

I kept writing poems, trying to please her, to be like her. My poems got longer and longer, ideas and images evolved into sentences, and then paragraphs, until she said to me, “You are not a poet.” It was a blessing. What she meant was, “You are not me.” Which was another way of saying, “You are free to be you.” I never wrote another poem again.

My mother and I wrote about the same thing: her life. But my mother was drawn to the natural world, politics, and the soul; I was interested mainly in people, those I made up and those who I knew. My mother enjoyed people insofar as she observed them. The people she liked she called “characters,” as in “So-and-so is such a character.” In the South of her childhood, being called a character was a great compliment. It was more than being deemed worthy of playing a role in a story. It was to be a story in and of oneself.

I showed my mother all of my writing. In college, I composed an essay about a time when she slapped me across the face. I titled it, “The Slap.” I had sent it to my mother, and she had returned it with corrections and suggestions in the margin. In the letter that accompanied her edits, she paid me what I felt at the time was a great compliment. She wrote, “I hardly recognized myself. It was as if I were reading about someone else entirely.” In transforming my mother into a character, I had, I felt, given her back the gift she had given me: herself.

PROMISE

“Folks, we're watching the kettle boil,” Mr. Hayden said to the crowd admiring the young woman who would become my mother. How I treasured this story.

Langston Hughes was a friend of Robert Hayden’s. When he was looking for an assistant, he came to Fisk and asked Hayden to introduce him to his most promising students. On the day that my mother was scheduled to meet Hughes, she came down with the whooping cough. Hayden introduced Hughes to George Bass, who became Hughes’s secretary and literary assistant right after graduation. My mother eventually went to medical school, where she and my father began their romance.

It is because of this story that I became interested in Langston Hughes. It is precisely because of this story that I eventually edited a collection of letters between Hughes and his longtime friend, writer and arts patron Carl Van Vechten.

CIRCLE

Dr. Allen was my father's mentor when he was a student at Meharry Medical College. Like my father, he was an OB/GYN. Also like my father, Dr. Allen was from the Caribbean. His wife was a woman like my mother, in that people admired her and saw her as the moral anchor of the family. Not long after he retired, Dr. Allen suffered a massive stroke.

My mother took me with her on a visit to the Allens during my first year in graduate school, which had been difficult. Becoming a scholar, it seemed, required approaching stories as objects to study as opposed to sources of pleasure. After a year of wrestling with this new way of looking at books, I was finally at home with my mother, and free to spend the summer loving language the way she had taught me to do. I was 23. We had come from church; they lived a few blocks away. I was happy; so was my mother. The sun was shining, and we were together, just the two of us.

Visiting loved ones on Sundays was a ritual both my mother and the Allens had enjoyed in their respective childhoods. As a child, I hated this ritual, which my mother called, simply, “visiting.” I was bored. As a young adult, however, I enjoyed this ceremony that had so shaped my mother’s childhood. It made me feel close to her.

“Daddy.” Mrs. Allen appeared from the recesses of the house. No matter the time, their house was always ready for us, always immaculate, photographs of their accomplished children in gilded frames on mahogany side tables; pristine chairs and loveseats in romantic, muted gradations of red, protected by plastic film. It was a house in which one always sat up straight. Mrs. Allen reminded her husband about his medication.

Since the stroke, their roles had reversed. Now she was the boss, and her voice was full of new authority. “Yes, Mommy.” That’s what Dr. Allen called his wife. He accepted the new order of things. He had no choice.

After the usual exchange of pleasantries, my mother and I got up to go. I was relieved. The stroke had deprived Dr. Allen of the power of clear speech. It had been painful to listen to him stammer out the simplest of phrases.

“OK,” my mother said, smiling her genteel smile. She reached for Dr. Allen’s hand as he stood slowly. It was a magnanimous gesture on her part. She was naturally reserved, affectionate with her children but not given to touching people outside of the family. Inch by inch, Dr. Allen rose, but he didn’t let go of her hand.

I knew our good-byes would take a while; they always did. But this time, Dr. Allen had a determined look in his eye. He had something to say. It took all of the strength he could muster to get the something out.

“Y-y-our mother,” he started. “Y-y-our mother.” And he proceeded to tell a story about my mother before she was a mother, when she was, like my father, a student at Meharry Medical College.

I learned that my mother had been his prized student, much more talented than my father. He told her, as her father had told her, that she could have a great future in medicine. “I would rather be married to a doctor than be one,” was my mother’s response. Instead of a physician, my mother became a medical technician, and abandoned that profession once she married my father.

“I would rather be married…” He kept his hand on my mother’s arm “…to a doctor…” My mother put her hand on my arm. I felt the pressure of her fingers. “…than be one.”

Dr. Allen had offered my mother an elevation, a rank above women. She had dared to reject him. She had paid a price. He knew it; we all knew it. We made a perfect circle, the three of us: past, present, and future. My mother’s slim fingers pressed and pressed into my wrist.

My mother and I got into her car, a Toyota. She never drove my father’s Mercedes, not once. To her, it was frivolous. But my father was boss; he said what was what.

She suggested we visit the nearby farmer’s market. I agreed. We didn’t speak of what Dr. Allen said. I ached to do so, but I was embarrassed—embarrassed for her.

I was 23. I didn’t know then what I know now, which is that the person Dr. Allen described was just a person that my mother had been. Nearly 30 years later, I myself have been many people, some of whom I am proud, some of whom I am ashamed.

STOLEN

I was in New Haven when my brother Warren called me. I was in my late 20s and deep into the work of my first book, a collection of letters between Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten. I was just back from the library when the phone rang.

“Mom says you took her book,” Warren said. He sounded weary. I could tell from his voice that he had no heart for this phone call. “She says you have her book of letters by Langston Hughes.”

I could hear the staccato muttering of my mother in the background. I pictured her busily sifting through piles of books on the floor of her room, her voice growing sharper as she searched. The brilliant young scientist, the gifted young poet, lived somewhere in the shadows of this middle-aged woman, my mother. The in-between years, rife as they were with loneliness and depression, had not been kind, but those young women were somewhere in there, still.

“She wants it back,” Warren said.

“Tell her I’ll send it to her,” I told him.

My mother and I never spoke of this phone call, her confusion, or what it meant, but it changed something between us, and revealed a divide that never healed.

“She felt you stole her life,” a friend said when I told him this story. It occurs to me now that in fact I did.

THE END

In our last conversation, my mother told me that I needed to change. I harbored too much anger about the past, she said. She meant my father. The anger would only cause me pain in the end, she warned. I had to learn to forgive.

“Don’t leave your father out,” she said. I promised her that I wouldn’t. It’s hard for me to believe that she didn’t know, on some level, that we would never see each other again.

While we were talking, my father walked by.

“How are you doing, mother?” he asked.

“I’m fine, Daddy.” He put his hand on her shoulder and they laughed together.

“You and Dad are getting along so well,” I said after he left the room. It was only a point of observation.

My mother looked at me with a level of incredulity that was almost theatrical. “Emily, that’s the nicest thing you’ve ever said about my marriage,” she said.

HOME (2)

Two years ago, my husband, twin daughters, and I moved from a small house to a bigger house. Neither my mother nor my father was alive to see our new house, which is not unlike the house I grew up in. But as much as I try, the similarity is only on the surface. I can’t seem to replicate what I most admired about the interior of my mother’s home, which is her sense of order.

John, the girls, and I went to family therapy once. It was my idea, mostly just a plot to get us all in the same room.

The therapist asked us each to say what we wanted that we weren’t getting from the family. The girls complained about each other, and then complained about how much we complained about them. I said I wanted more peace in my home, more relief from the girls’ continuous skirmishes. John said, “I just want people to put their things away.”

One of the reasons that we moved into a bigger house was because I wanted more space in which to write. I chose the largest bedroom and made it into a writing studio. It took months to decide on the right shade for the walls, and then weeks more to find the perfect textures and patterns for the daybed and the rug. Two years after our move, the walls in my writing space are still bare.

Every surface in that room, though, is covered in my stuff. It’s gotten to the point where I can barely enter the space without experiencing overwhelming anxiety. Typically, I work at the kitchen table, which is almost always clean because of my tidy husband.

“You colonize every space in the house,” John scolds me from time to time. But mostly he has given up on changing me. When he finds checks addressed to me next to the drying rack, he puts them on top of my books on the counter without a word.

Often I am seized with guilt about how rarely I prepare a meal for my family, and how much space I take up, but I can’t seem to reform, even though I regularly pledge to do so. Sometimes I imagine I can sense John’s resentment radiating from his back while he is at the stove, creating that evening’s meal in pots, pans, and skillets. In general, however, he refuses my help. Once Giulia came in while I was busy with work at the counter. She shot me a look and then loudly offered to assist her father. He gruffly shooed her away. She stomped out of the room.

“Why did you marry him?” Giulia sometimes asks me after moments like these.

“Maybe you’ll make a different kind of choice,” I always tell her.

Recently, I teased her about this routine, assuming it was ours alone.

“I ask Daddy the same question about you,” she told me.

As eager as I am to find out, I have never asked her how he responds.