1. Commonplace

The Wrong Daddy

Morrissey and the cult of the wounded white male

Jeremy Atherton Lin

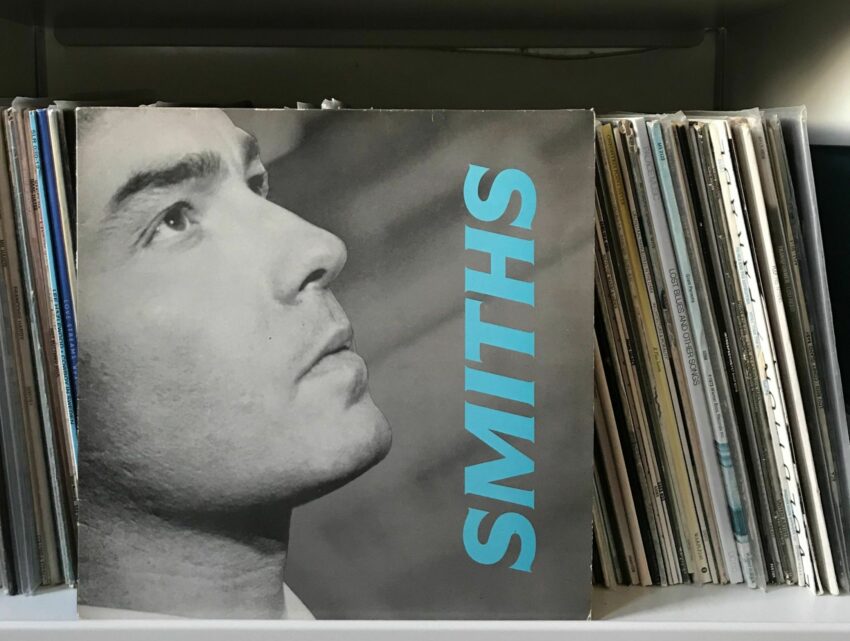

I first saw the object in someone else’s hands. She was a teenager at Vallco, the most comprehensive shopping mall in the Silicon Valley. This was 1986 or so, when I was not yet teenaged myself. I watched her pull the twelve-inch square out of her Rainbow Records bag. Roughly half the plane, though it seemed like more, was occupied by one man’s face. Even in severe close-up, cropping out cues like hairstyle or shirt collar, he had the look of a chap from decades before—from back when the world was safe, watched over by strong-jawed fathers.

The man conveyed a respectable anonymity. (Much later I’d learn that he was Richard Bradford, an American actor known for his role as a private eye on the British TV series Man in a Suitcase.) His angle is one of reverence, forty-five faithful degrees. He could have been a priest, or Joan of Arc in the silent film. He could have been on his knees about to pray—or give head. Maybe he was just filled with ennui. In front of him, electric blue letters, italicized and sideways, spelled out “SMITHS.”

The ascetic design seemed far more sophisticated than what I’d hitherto known. I’d started out buying records by Duran Duran and the Go-Go’s, bands with recursive names and album artwork crowded with ancient palimpsests and party bunting. But here a process of extraction had occurred, and what was left was stripped so bare it was almost embarrassing to see. The cover also depicted a specific kind of manhood—generic, taciturn, self-contained. In this man’s presence, I’d be clumsy, unintentionally speak too loudly. The stoic became an object of desire. Though the cover did not state the name of the single, “Panic,” it elicited in me that febrile state of being.

By thirteen, I’d become devoted to the band. In the suburbs of northern California, I felt adrift. The sunshine and manicured lawns that surrounded me could not be my natural habitat; I belonged somewhere more historical, and gloomier. I found my place through the Smiths. The band, a product of post-industrialism, formed in 1982 in Manchester, England, where, under Margaret Thatcher, manufacturing was in decline and unemployment on the rise. Fronted by the beguilingly maudlin, lizardy, weird-sexy lead singer Morrissey, the Smiths had little truck with the New Wave flourishes—teased hair, pirate blouses—of acts like Dead or Alive and Adam Ant; instead, their look was more akin to a style dubbed “hard times” in the September 1982 issue of The Face—distressed, rockabilly-tinged, Dust Bowl-ish, evincing downbeat economic realities.

morrissey, born in 1959 to Irish immigrants in a Lancashire town outside Manchester, came to embody a caustic and erudite distillation of northern English working-class sensibilities. His lyrics, wrapped around Johnny Marr’s distinctively jangly guitar lines, tackled economic disparity (“England is mine, it owes me a living”), and his public comments cut straight to the mendacity of powerful politicians.

Morrissey constructed himself as an unlikely bard of the common people. In place of Thatcher or the queen, his national treasures were the saturnine playwright Shelagh Delaney and the bouffanted Viv Nicholson, who flamboyantly squandered the small fortune her husband won gambling. Morrissey’s spotlighting of working-class figures could be vital and productive. But he tended to fix his gaze on a certain point in history, some time in the era of his youth. He made icons of a photogenic few while dismissing the rest as hoi polloi. “Birds abstain from song in postwar industrial Manchester, where the 1960s will not swing, and where the locals are the opposite of worldly,” he wrote in his autobiography. Rendering a subtly camp vernacular from this provincialism, Morrissey aestheticized a partial, and mostly whitewashed, image of the working class. I was yet to grasp all this consciously: I came into an aesthetic the way young people do, in a conundrum of longing and envy.

2. shirtlifter

I was compelled, too, by the post-Warhol sameness and replication of Morrissey’s art direction. The Smiths’ cover artwork comprised a procession of faces: when they weren’t brash working-class women, they were statuesque white men in banal clothing. It was a homo that was distanced from the sexual. “I hate this ‘festive faggot’ thing,” Morrissey proclaimed of gay culture in 1984. People said he was celibate, which made him attractively hard to get. He was a pinup for the closet, expert in imperious denial: “I’m not embarrassed about the word ‘gay,’ but it’s not in the least bit relevant. I’m beyond that frankly,” he said in an interview in 1985. (Weirdly, few seemed to talk about the significance of a sexually abstinent pop star rising to fame at the time of the spread of AIDS.)

The band’s sparkling second single, “This Charming Man,” tells of a lad who gets into the car of a flirtatious gentleman. The song was as chaste and codified as Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Relax” (released a week earlier) was smutty and overt. Words like charming and handsome gleamed like polished antiques; the syntax of hillside desolate was archaic. Even when Morrissey’s lyrics were forthright, as in the song “Miserable Lie,” the sex remained awkward: “I know that windswept, mystical air / It means: I’d like to see your underwear.” This was reassuring to someone like me, as desperate to be corrupted as I was terrified by penetration. We Smiths fans kept our undies on.

There was nobody to enlighten us as to how ordinary, classic, and regular, like neutral, had been constructed by a culture dominated by whiteness.

In place of copulation, the Smiths extolled stalking, hesitation, repulsion, disavowal. This provided me with a model for deflection: Instead of being gay, I could be what the critic Richard Dyer identifies as “the sad young man”—as Dyer points out, generally meaning “sad young white man”—a paradoxically impermanent archetype in literature, “moving between normal and queer worlds, always caught at the moment of exploration and discovery.”

I was enthralled by an older Smiths fan named Aaron. He worked the lightboard at the theater where I ushered. He had a serious, sensuous face, with hair lying close to his scalp in golden waves. He passed close by me in the lobby once, wearing a necktie as a belt, its length dangling along his thigh. I was deeply impressed. Not long after that, Aaron shot himself in the head. It was said he did so in his bedroom beneath a giant poster for the Smiths’ single “Shoplifters of the World Unite.” I fought against imagining his shattered brains on the wall.

A lot of kids kill themselves in the aspirational county where I was raised. But Aaron’s suicide seemed to me specifically homosexual. Only recently did I learn that shirtlifter was once a British slur for gay men; the phrase “Shoplifters of the World Unite” may be Morrissey’s play on words. I can’t imagine that Aaron would have been any more alert to this reference than I was; we had no way of learning about that kind of history. We had only our intuition about the atmosphere around such codes.

3. the sun and the air

After moving to London in my thirties, I rediscovered that “Panic” twelve-inch in a basement record shop. I purchased it, finally, and marveled that the dour cover had captured the attention of my very young self. I then set out to write a memoir about growing up out of place—a Smiths fan in the California suburbs. I titled the manuscript “The Sun and the Air”—a mondegreen of “the son and the heir” from the Smiths song “How Soon Is Now.” My homophonic misapprehension goes some way toward demonstrating how I construed in the band something elemental, transcendent. The actual verse is, “I am the son / And the heir / Of nothing in particular,” a culturally specific reference to bloodlines, to the lack of title or entitlement. But I had taken Morrissey’s post-industrial landscape of iron bridges and grim side streets as poetic invention and the spiritual home for my own awkward puberty.

In Saint Morrissey: A Portrait of This Charming Man by an Alarming Fan (2003), the critic Mark Simpson coined the portmanteau melanalgia (combining melancholy with nostalgia) to describe how Morrissey’s lyrics pine for the England of a gritty yet spectral past. To Simpson, who actually grew up in England, melanalgia meant wearing secondhand clothes and checking foxed books out of the library, pointedly reacting against the slick 1980s status quo. To the sect of American teens to which I belonged, it meant identifying ourselves as alternative. The term wasn’t futuristic or utopian; instead, we donned makeshift signifiers of authenticity from eras past. At Savers, a sprawling thrift store, I sought out the hand-me-downs of strangers. I particularly loved a scratchy green cardigan the hue of an artificial Christmas tree. We traded optimistic, aggressive Americana (cheerleading, drinking from kegs, weight machines, jeeps) for the chalky terroir of old England. Though I had near-perfect vision, I was always looking out for a pair of bulky spectacles like the ones Brits got for free from the National Health Service. Morrissey wore a pair like that. He adorned himself in meretricious stigmas such as Band-Aids and hearing aids to accentuate his alluring vulnerability. Like him, we wanted to look wounded.

Morrissey emboldened my sense of disaffection through songs like “What Difference Does it Make?” and humored my persecution complex in songs like “Unloveable.” I responded to his historicized English landscape because I saw myself in it—a romantically anemic, damp, pitiable, somehow justified version of myself. I wanted to be, as the press called Morrissey, “pale and interesting.”

4. common name

When fans talk about the Smiths, they talk about themselves. They testify that Morrissey’s lyrics seemed to speak just to me. I knew as much but remained convinced that my own elision of fandom and autobiography was somehow idiosyncratic enough to merit pursuing at book length. I got down tens of thousands of yearning, impetuous words. What I didn’t grasp was that a meaningful study of my connection to the band would require me to expose a rupture.

As a boy, I had been told that Smith was the most common name. I saw commonness as an honor. I envied every Smith I knew, all of them blonds; I failed to note the many Smiths of color. In a 1984 interview on Good Morning Britain, Morrissey said of the band name: “It really had to be as basic as humanly possible.… It’s the most popular name in the universe, nearly…” The host interjected: “Outside of a couple of Chinese ones, which wouldn’t have gone down too well in this market.” Morrissey demurred with a grimace. For my part, I tried to take consolation when my father informed me that Lin was a Mandarin equivalent of Smith—a ubiquitous name in China, meaning “forest.” But it did not have the trustworthiness of the Old English patronym, as derived from blacksmith—a reliable, hardworking appellation.

In my inchoate memoir, I fixated on my compulsion to blend in, be undetectable. I was the son of a Chinese immigrant writing about the urge to achieve anonymity through manifesting an essential Englishness. I invoked Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari: “To go unnoticed is by no means easy. To be a stranger, even to one’s doorman or neighbours.… This requires much asceticism, much sobriety, much creative involution: an English elegance, an English fabric, blend in with the walls, eliminate the too-perceived, the too-much-to-be-perceived.” My proclivity for white Englishness wasn’t totally extrinsic—I’m of Anglo matrilineage. In Morrissey (and in his stand-in on the cover of “Panic,” or in his other heroes/surrogates, like James Dean and Little Joe from Warhol’s Factory), I sought compensation for what I took to be the disapproval of white males in my extended family. I latched onto Morrissey’s perpetual ambivalence. I didn’t have to impress Morrissey; I could imagine his affection as a remote possibility. Morrissey loves you, we all love you, a friend wrote in my yearbook. (The icon was ours to ventriloquize like that.) Yet I wasn’t obsessed with Morrissey in order to feel seen but because he looked the other way.

Even in his most miserable depictions of Britain, Morrissey helped mythologize it as a place to be cherished as waves of foreigners erode it. Long before he left, Morrissey dwelled in the old country.

In 1991, my junior year in high school, Morrissey, by then a solo artist, released the song “Asian Rut,” about three white lads beating a druggy, vengeful Asian boy. The narrative was ostensibly a nuanced condemnation of racial conflict, but it was told in a manner at once fetishistic and phlegmatic. My Asian American friends and I giggled uncomfortably over the title. We understood that in Britain, Asian referred to the subcontinent, to Pakistan and Bangladesh; our ancestors were from China and Korea. Still, it felt personal. We detected a vague chauvinism cast over Morrissey’s perspective, as in his 1988 song “Bengali in Platforms,” with its vexing line “Life is hard enough when you belong here.” I felt seen, but in a creepy way, as in sussed out.

But Smiths fandom proved hard to outgrow. After moving to New York City, Ben, my Korean American friend, magnetic and as “out” as could be in high school, began to cohost a night inspired by the band at a club called Sway. The weekly event had no name, so people referred to it however they wanted, keeping its image low-key and cool. Soon enough “It began to draw crowds, first of downtown scene-making types, later of celebrities.” That line was from Ben’s 2017 obituary in The New York Times, headlined “Death of a Downtown Icon” to chime with the Smiths song “Death of a Disco Dancer.” At his funeral, a gospel choir performed another, “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out,” and those words were illuminated in LED.

When we were in our twenties, Ben regaled us with the tale of spotting Morrissey at a restaurant in Los Angeles. He’d been in the presence of big papa, as he put it. Or would he have spelled it like the Notorious B.I.G.: “Big Poppa”? Either way, it put in mind the Indian American girl at the high school next to ours who legally changed her surname to Morrissey at sixteen. This idol worship seemed tongue in cheek and yet obviously committed and strangely devoid of any introspection about why we all yearned for a grumpy white daddy. Maybe on some level we thought our purchase on Morrissey and his doppelgangers—the ordinary aesthetic, classic grooming tics, regular fit jeans—was empowering. There was nobody to enlighten us as to how ordinary, classic, and regular, like neutral, had been constructed by a culture dominated by whiteness. What’s more, alternative may have been just a different shade: even whiter.

5. big papa

I figured Ben’s funny, slightly icky nickname for Morrissey had been spontaneously put, a one-off. Recently, my brother-in-law Euan was strolling in a park in Los Angeles when a Chicano man approached, calling “Hey, big papa!” and offering him a protracted handshake. At some point, Euan realized he was being mistaken for Morrissey.

By now, it’s well known that the singer has a lot of Latinx fans. In a 2017 TEDx Talk, Gabriel Avalos, an earnest Mexican American teenager, wearing a blazer over his Smiths T-shirt, almost tripping as he walks onto the stage, advances the theory that while artists typically define the fans, in this case the fans have redefined the artist. Other devotees wear T-shirts that transpose Morrissey’s song “Irish Blood, English Heart” to “Mexican Blood, American Heart.” The symbol riffs on Mexico’s coat of arms, adding an American bald eagle to the Mexican golden eagle devouring a rattlesnake while perched on a prickly pear cactus.

Morrissey has professed his fondness for Mexico, donned a Chivas jersey, and written a song called “Mexico” to lambast inequality across the border: “If you’re rich and you’re white / You think you’re so right / I just don’t see why this should be so.” Writing in The Guardian, Raf Noboa y Rivera describes a shared “sense of estrangement and longing” that links the lyrics of Morrissey’s ballads and those of Ranchera, a northern Mexican folk-music tradition. “My family has myriad tales of living in a golden Mexico during the 1940s and 1950s,” he writes. “Those stories helped foster a deep-seated melancholy within me about where I truly belong. Not quite American; not wholly Latino, living in all the spaces in between.”

The etymology of the word nostalgia combines Greek nostos (a return to home or native land) with algos (pain or suffering). It was once a medical term for homesickness, considered to be a physical disease. The historian David Lowenthal explains that by the seventeenth century, immigrants who had languished or perished were considered to have been enfeebled by dislocation from their homeland; bodies that succumbed to meningitis or tuberculosis or malnutrition were said to be nostalgic. “Today,” the critic Carol Mavor wrote in 2007, “nostalgia is a disease of longing, sociocultural and not medical.”

That year, Morrissey lamented the impact of immigration on his homeland: “England is a memory now,” he said. Curry and reggae had come to be considered national heritage, evidence of a pluralistic society. I had my own part in spoiling the English identity, I guess: I relocated there a few months before he made that comment. Morrissey himself had done the reverse, moving to Los Angeles in 1995. “The England that I have loved, and I have sung about and whose death I have sung about, I felt had finally slipped away,” he said about his expatriation. With that statement, he laid bare how he—the son of immigrants—authored his own England, a willful confabulation. Even in his most miserable depictions of Britain, Morrissey helped mythologize it as a place to be cherished as waves of foreigners erode it. Long before he left, Morrissey dwelled in the old country.

6. apologist

Morrissey is not a racist. So stated, with whatever amount of sincerity, the editors of NME in a 2012 apology after Morrissey sued the magazine for suggesting otherwise. Then in 2019, the singer proclaimed the word racist meaningless. “If you call someone racist in modern Britain you are telling them you have run out of words,” he said. “You are shutting the debate down and running off. The word is meaningless now. Everyone ultimately prefers their own race—does this make everyone racist?”

As I toiled over my prose about being his fan, Morrissey would periodically pass remarks like that. He spoke of how the Chinese could be a “subspecies,” considering their record on animal welfare, and how London has been debased by a British Pakistani mayor who “cannot talk properly.” On late-night TV, Morrissey wore the badge of a far-right U.K. political party whose leader has focused on quashing Muslim immigration. I tried to take his outbursts in stride, to fix my narrative in the past, as if the past is fixed. But revisiting his lyrics, I began to find them more vituperative, less empathetic than I’d recalled. A song’s narrator would be woefully misunderstood, but that was because he was surrounded by the dim-witted and distinctly othered: women buck-toothed and monstrous; gay pederasts; Bengalis who don’t belong. Whereas I’d once positioned the singer in a coalition of outcasts, I began to see him as sneering at the rest.

In his essay “The White to Be Angry,” the critic José Esteban Muñoz revisits the lyrics of X, his favorite band as a teenager. Their anthemic song “Los Angeles” describes a resident of the city who finds herself hating Blacks, Jews, Mexicans, and gays. It’s an allegory about white flight, but listeners may suspect the message is as collusive as critical. Muñoz, a Cuban American, writes:

Though queerness was already a powerful polarity in my life, and the hissing pronunciation of “Mexican” that the song produced felt very much like the epithet “spic,” with which I had a great deal of experience, I somehow found a way to resist these identifications. The luxury of hindsight lets me understand that I needed X and the possibility of subculture it promised at that moment to withstand the identity-eroding effects of normativity. I was able to enact a certain misrecognition that let me imagine myself as something other than queer or racialized. But such a misrecognition demands a certain toll…to find self within the dominant public sphere, we need to deny self.

Self-denial is a tricky position from which to write memoir. Ultimately, I was relieved to abandon “The Sun and the Air.” You’d have been brought onto the radio, a friend laughed, and introduced as a Morrissey apologist.

7. weirdos and misfits

In early 2020, Dominic Cummings—then chief special adviser to Prime Minister Boris Johnson and architect of the victorious Brexit campaign—posted a job recruitment notice for “weirdos and misfits with odd skills.” This jargon, and the jobseekers it attracted, came under scrutiny after one new hire was forced to resign; comments he’d made in support of eugenics had surfaced. The “weirdos and misfits” line struck me as in accord with the way alternative was now being bandied about—as in alt-right, or alternative facts.

In my youth, “alternative” connoted, or so I thought, not only a position on the social margins, but the open-border policy there. At some point, the word flipped to mean angry white people with abandonment issues, the far-right fringe. I’m forced to consider that the subculture I’d participated in, by centering the narrative of wounded white men, might have laid foundations for this consequential turn. Looking back, what was alternative without bitterness, pasty complexions, hatred of the contemporary, feelings of ostracization, moping? The alternative scene was basically angry white people with abandonment issues. Morrissey’s England was depressing yet glorious, an island in the doldrums, yet halcyon, white—the very place members of today’s alt-right want to paddle back to.

Mid- to late-period Morrissey, paunchy, remote-eyed, spouts off a rose-tinted jeremiad about the loss of identity. He’s pretty zeitgeisty that way. Just recently a poll showed that nearly a third of England’s adult residents, hot off leaving the European Union, would also vote in favor of independence from the United Kingdom, despite London being the center of power and seat of government. The academic Alex Niven responded in The Guardian: “One of the major problems with contemporary debates about ‘Englishness’ is that England does not really exist as either a coherent or a concrete political reality.” Niven cites the historian Benedict Anderson’s concept of “imagined communities,” which are drummed up to foster a sense of shared belonging. “England,” Niven proposes, being scarce of political institutions that differentiate it from Britain as a whole, “can mean pretty much whatever people want it to mean.” England, to amend Morrissey, is now a false memory.

“Why did you call yourselves the Smiths?” a schoolboy asked the band on a children’s TV show in 1984. “Because it was the most ordinary name,” replies Morrissey, almost teacherly, “and I think it’s time that the ordinary folk of the world showed their faces.” I admired that class consciousness. It took much longer to recognize that Morrissey saw ordinariness in his own image, a perspective that can slide into “Make ________ great again” politics. I’m not sure there’s a place for (mixed-race, faggoty) me in that mythical past.

When I was an alternative teenager, uneasy in the present, I sought refuge in the retro. The fashion statement of my anachronistic green cardigan was, basically, History is worth repeating. In truth, against my skin, it wasn’t a great look. But I was a Smiths fan, charmingly old-fashioned, thriving in disjunction from my surroundings. Today, having forsaken my idol, I’ve also exited the illusory country he inhabits. I can never go back to the house of the wrong daddy again.