Translated by Sophie Seita

Hidden Words

Searching for meaning in a rubber stamp

Uljana Wolf

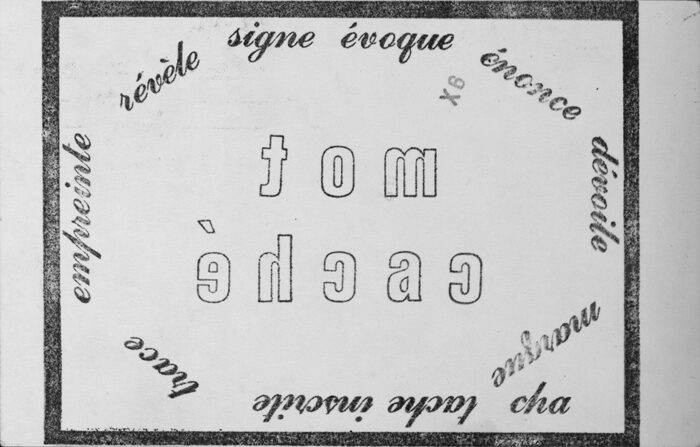

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Mot Caché, 1978. Courtesy the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

In 1978, theresa hak kyung cha made a stamp—a rubber stamp, not a postage stamp—for a small exhibition in Amsterdam. Cha, whose "mail art," writing, and performances explore patterns of public circulation, mistranslation, and exchange, made the stamp to fit on a standard postcard. At the stamp's center are two words, outlined in black: mot caché (French for "hidden word"). Arranged in an oval around them are other French words, in mirror image—empreinte révèle signe évoque énonce dévoile marque tache inscrite trace—all of which relate to the act of inscription.

After the stamp is applied to paper, the outer circle of words becomes legible. The words in the middle, however, hide themselves again. (They now say tom éhcac.) So the “correct expression,” at least in this mode and direction of reading, stays behind, on the stamp, elsewhere. The words of inscription wrap around the hidden word(s) like a glove, within which: a center that doesn’t send.

But there’s another word, too. In the lower right-hand corner of the stamp, uncapitalized: cha, Theresa’s family name. At first glance, the name lies outside the word circle of inscription. But if you look again, you notice that the name also lies buried within the phrase in the middle of the stamp, in the rearranged letters of the word caché. In this way, “cha” itself is the mot caché: the hidden word.

What exactly is being sent with this postcard? Is the hidden word meant to be a Korean name, or is it so untranslatable as to be absent, undetectable? Does everyone who sees the stamp or the postcard have access to the same hidden word? The same experience of displacement?

When I came across Dictee in New York a few years ago, it was like receiving a dispatch, a linguistic memo I didn’t understand. It stayed with me, this dispatch, because (I now realize) as a German poet writing mostly in the language I was raised in, I was and am always in search of paths that lead me away: away from the sorts of understanding that I’ve inherited; away from my ways of thinking as an East-, perhaps post-East-, perhaps multi-German writer; away from the categories of estrangement and non-estrangement in my life, which has long swung like a pendulum between New York and Berlin. For me, being a multilingual writer means that words are always inscribed with ghost-words. Cha’s work was particularly relevant to my experience of multilayered cultural and linguistic self-estrangement.

A postcard from Cha addressed to her brother John Cha and his family. A Mot Caché impression in black ink is stamped on one side. Courtesy the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

Dictee explores the same obsessions and methods that characterize Cha’s mail art: fragmentary, translingual language pointing to the failure of translation; documentary material questioning the possibility of singular memory; conversations that straddle multiple artistic mediums. In both the stamp and the book, Cha makes traceable what it means to be someone who has a language that is not “the right one,” not their own, not original or real—a language that exists only on a fantasized, distant, handmade stamp. A stamp perhaps like: home. Like: nation. Like: mother tongue.

When we use the term mother tongue, which language are we referring to? Just as the stamped image exists in an in-between realm, adrift and unbelonging, Dictee also demonstrates the failure to construct possible identifications through the actual language of the mother. Cha’s own mother, Cha Hyung Soon, grew up as a refugee in Manchuria, moving between the language of exile (Chinese), that of occupation (Japanese), and that of her ancestral country (Korean). For Cha, the search for heritage, for the place of the mother and her language, is not a search for a state of monolingual belonging. Rather: her rebellious longing is itself a form of latent asylum, a place unto itself.

From the very beginning, I knew that language was not to be found at home. Language was never in when I called. She wrote me joyously clumsy dispatches. One such note said Kochanie, the Polish word for darling. Then Gift, the German word for poison. Then the English word irritated, which doesn’t mean German irritiert (confused)—oh, false friends. These dispatches carried stamps in which I was multiply mirrored and hidden, a kind of redoubling that had to do with the invisible movement from Ost to Post-. Or with the fact that my inherited language was also the language of the Stasi, the East German secret police. Or with the fact that it was the language that my grandmother taught to Polish children as a young teacher in Silesia.

One could say that Cha’s failed translations and broken languages have an emancipatory function. Her work shows that family ties lie dormant in the hidden word, away from the language of inscription and registration. It shows that, in our broken, repetitive time, people can change identities, mothers become nations, nations become maids, and daughters become ferries. It shows that writing that radically interrogates the conditions of our linguistic and subjective becoming can make possible new, alternative, and more just forms of collective imagination. We take dictation, which we translate into new languages, words that we will become—words for others to receive.

Sophie Seita is a London-based artist, writer, and researcher whose work explores text in its various translations into book objects, performances, videos, or other languages and embodiments. More information on her performances, publications, and collaborations can be found at www.sophieseita.com.