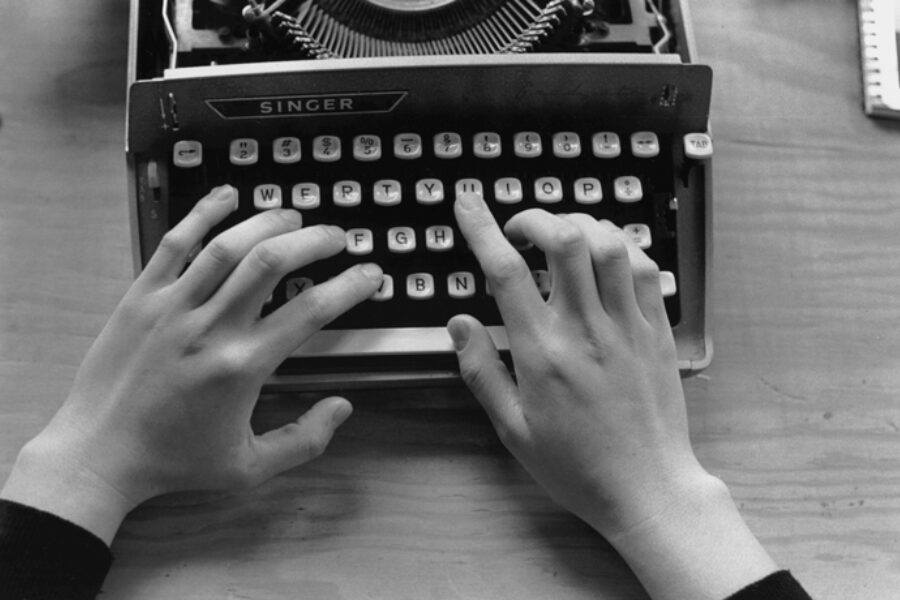

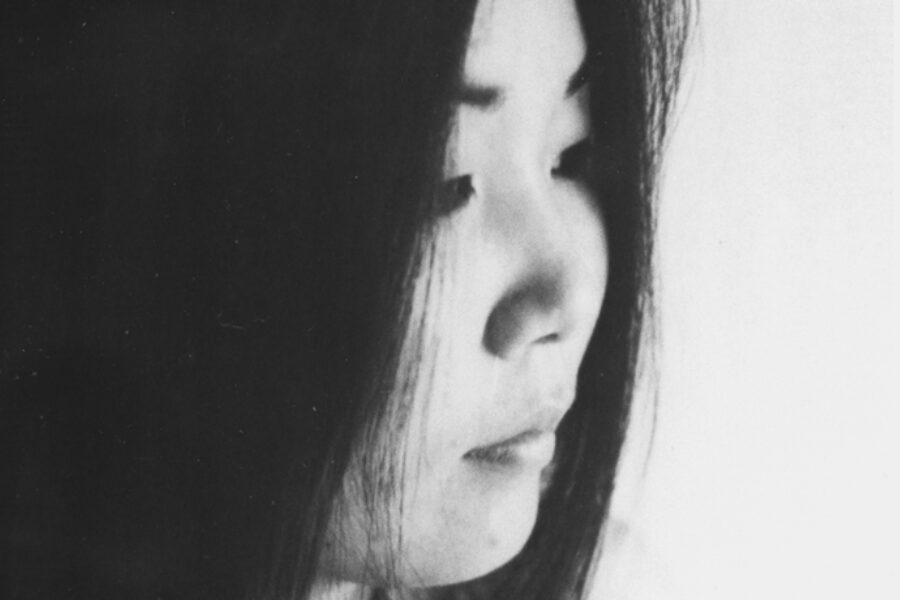

James Cha, Portrait of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, c. 1978. Courtesy the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

When writer and artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s experimental work Dictee arrived in the world forty years ago this September, it did so with little fanfare. Published in a small run by Tanam, a little independent press, Dictee was reviewed only by one or two close friends. But it quickly drew the attention of several fellow artists and critics who praised the work for its fusion of visual and literary practice, its uncompromising difficulty, and the new directions it opened both for Asian American literature and for American literature more generally. It took a little over a decade to establish its status as one of the most complex, subtle works of the era.

Cha’s life was notoriously taken, far too early, just months after Dictee’s publication, in a random act of sexual violence. Had she lived, she would now be seventy-one. She would have had students and acolytes; all the younger artists her work has reached, especially immigrants and women, would have been able to seek her out in person. She would have watched as Dictee became a mainstay of English departments over the last ten years. She could have attended the many symposia, retrospectives, and tributes dedicated to her work.

Dictee’s anniversary provides an opportunity to consider Cha’s remarkably wide influence and celebrate her monumental achievement. The Yale Review has invited five contributors—poet Ken Chen, writer Zahra Patterson, poet and translator Uljana Wolf, and visual artists Latipa and Yong Soon Min (the latter a friend of Cha’s)—to reflect on Cha, Dictee, and the book’s influence on their own work.

—the editors